Venturing into a tech revolution often starts with excitement and knee-jerk investments, which can result in a bubble that eventually pops.

Goldman Sachs thinks we aren’t in the bubble stage (yet), arguing that tech companies’ fundamentals are strong, valuations aren’t at previous bubble levels, many companies still have yet to benefit, expectations of long-term real growth are reasonable, and the stocks aren’t yet overly expensive relative to bonds.

To bet that Goldman’s right, consider investing in some established tech giants and a few emerging stars.

The stock market's been riding high on the AI wave all year, with top-performing companies seeing stunning gains on all the hype. But while some people are getting bubble jitters and seeing a resemblance to the heady days of the 1990s dot-com boom, Goldman Sachs says it’s not that. It says the tech sector is just at the start of a revolution. Here’s what it all means and how you might take advantage.

What’s Goldman’s view then?

The Wall Street investment bank acknowledges that something big is happening here. But it says it’s not bubble big (at least not now) – it’s revolution big.

And tech revolutions tend to follow a certain pattern. It looks like this:

Phase 1: The Emergence. A groundbreaking technology makes its debut and becomes the next big thing. Startups pop up everywhere and investors eagerly join the party. Stocks ride the wave, with soaring valuations that seem justified, given the projected tech-driven returns.

Phase 2: The Fervor. As the journey progresses, discerning the lasting impact of the tech becomes more challenging. Rather than being steered by rational analysis, stock prices are shifted by sentiment and narratives. Investors, now on the edge of their seats, invest more aggressively, pushing valuations to cliffhanger levels.

Phase 3: The Inevitable Shift. And then, just when confidence is at its peak, the tech bubble bursts. This pattern isn't new: research on 51 major tech innovations from 1825 to 2000 found price bubbles in a staggering 73% of cases. In this phase, a lot of startups will falter, leaving only the true innovators standing, left to push technological boundaries and introduce new economic narratives.

Phase 4: Evolution And Expansion. New tech spinoffs spring out of the remains of that tattered bubble, giving life to innovative businesses that benefit from the original technology's widespread acceptance. At the same time, established industries are forced to either adapt to the new tech or risk irrelevance. These developments can do a lot of things – introduce new job roles, drive consumer demand, and even enhance productivity – but this evolution tends to materialize only after the technology is absolutely everywhere.

So could AI already be in that bubble phase?

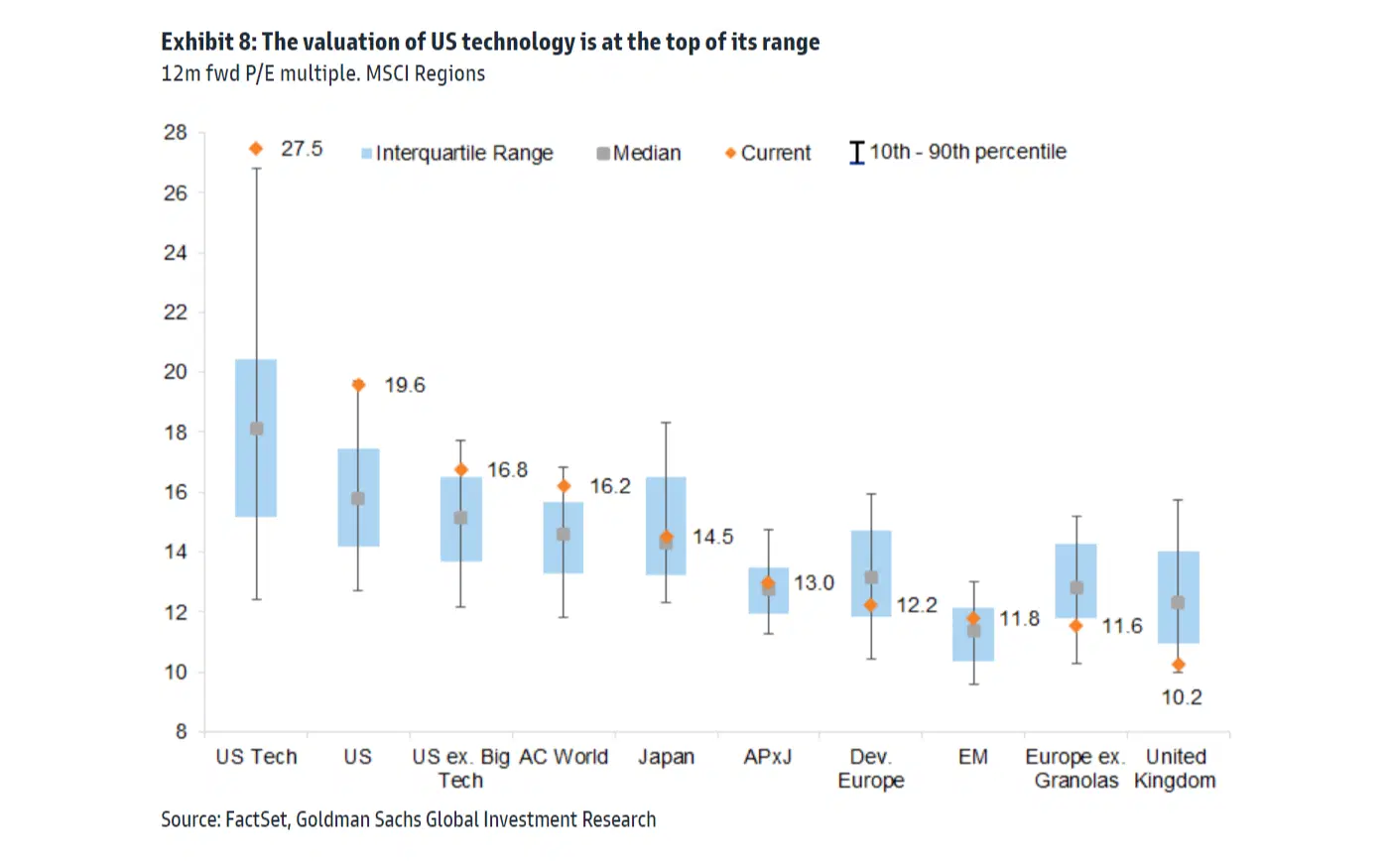

Many investors think it is, and it’s easy to see why: its spectacular gains have been driven by just a handful of companies, and US tech stocks are already trading at elevated valuations – not just relative to their own history but also relative to tech stocks in other markets. What’s more, this is all happening in the context of higher interest rates, which should be bad for tech stocks and show that investors have extremely optimistic expectations in terms of earnings growth.

US tech stocks aren’t just expensive relative to their own history but also relative to other sectors and regions. Source: Goldman Sachs

But Goldman says that, although AI may eventually reach bubble territory, it’s not there yet. Here’s why, according to its research:

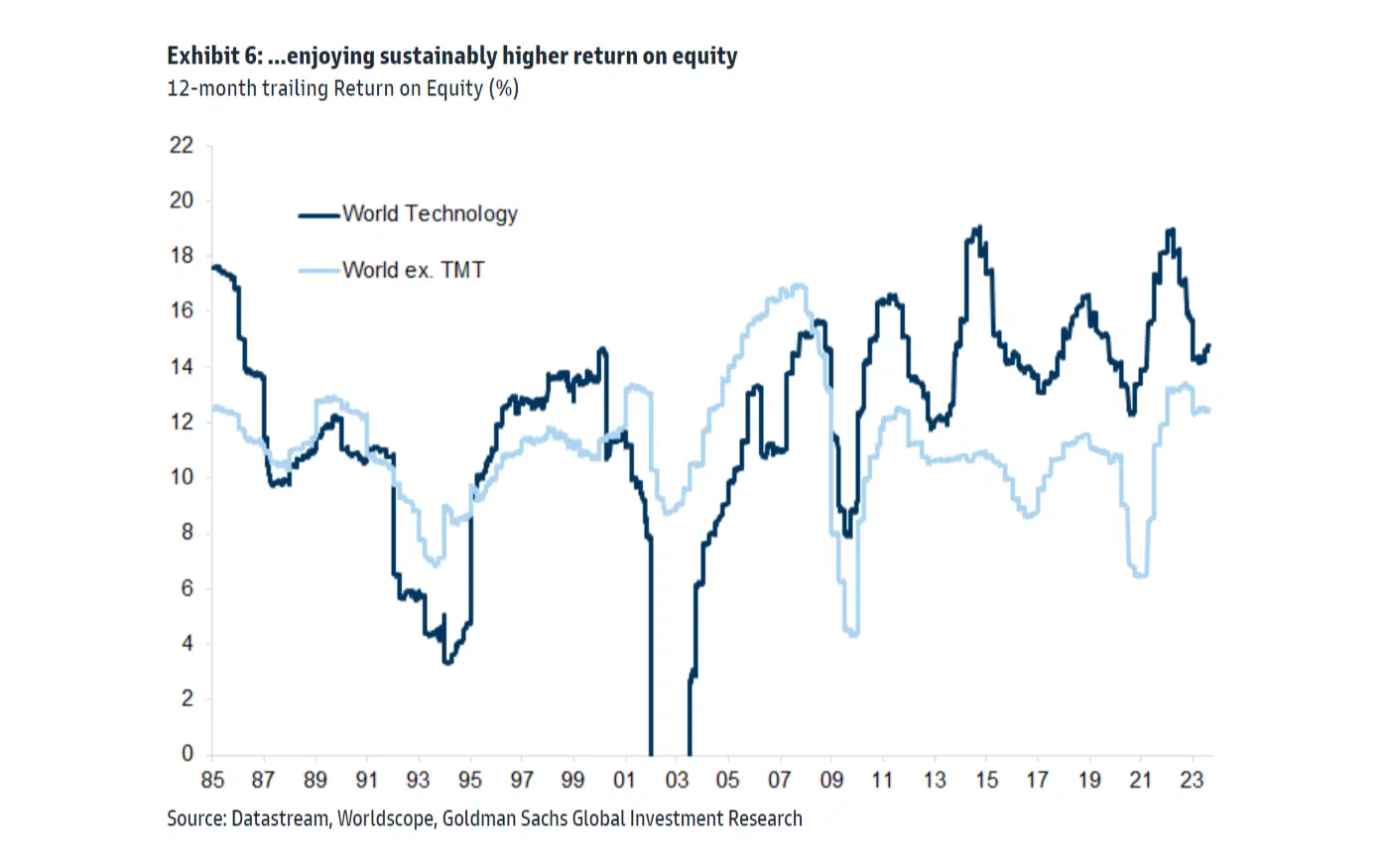

Fundamentals are strong

The strong performance of the tech sector isn’t new: it started more than a decade ago, and companies have demonstrated year after year that they’re worth the interest. And the tech sector hasn’t just enjoyed better earnings growth than other sectors, but it’s also earned a sustainably higher return on equity. What’s more, the current crop of leaders is already very profitable and generating a lot of cash, allowing them to invest in research and development and consolidate their dominant position, which makes them more defensive. And unlike in previous bubbles, investors today are favoring profitable companies over unprofitable ones, a healthy sign that shows they’re still grounded in fundamentals.

Tech stocks around the globe (dark blue line) have been seeing a higher return on equity than stocks in other sectors (light blue). Source: Goldman Sachs.

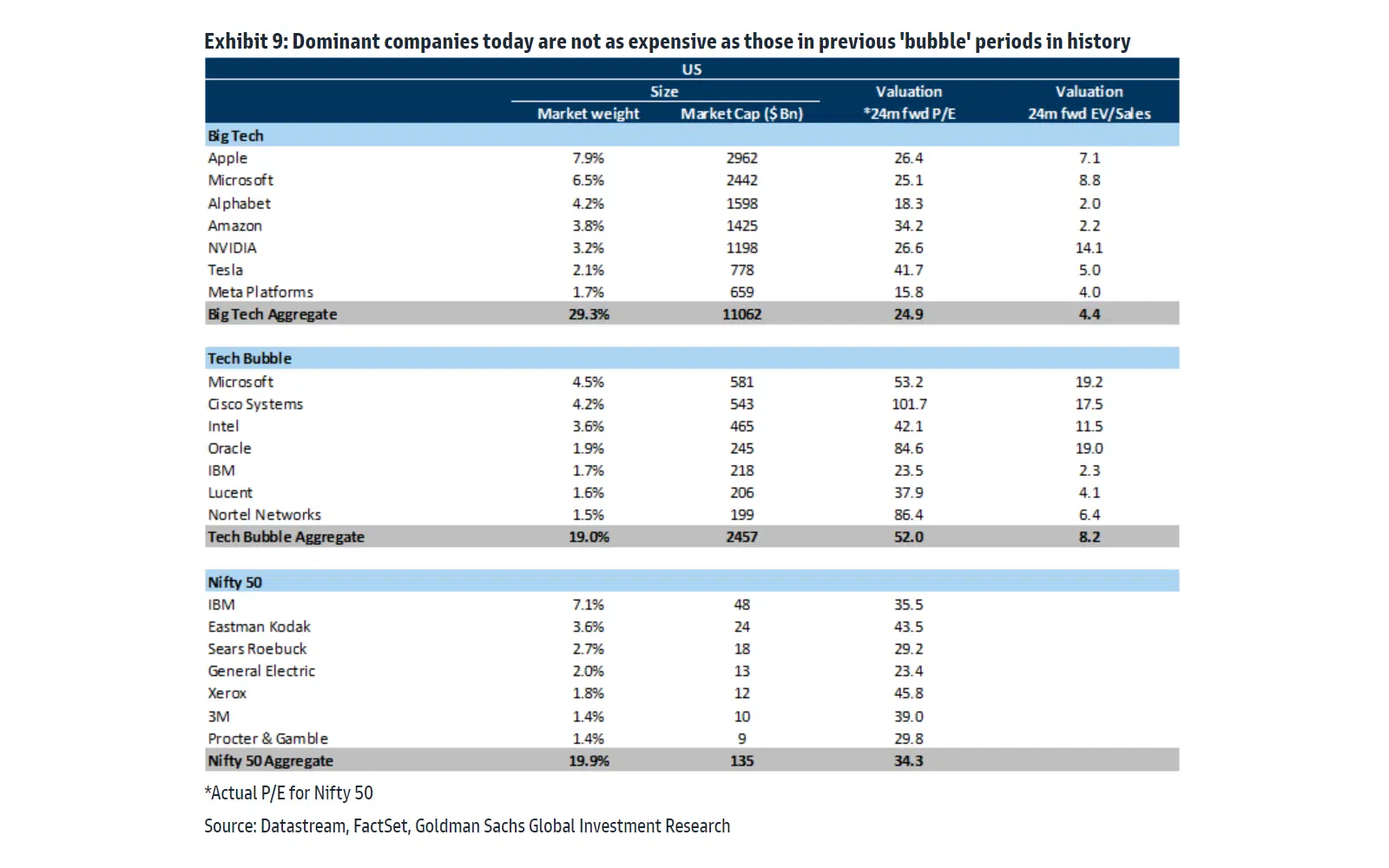

Valuations aren’t extremely expensive

While current valuations might raise eyebrows, they haven't reached the dizzying heights of past bubbles. Case in point: the seven US tech giants at the AI forefront boast an average price-to-earnings ratio of 25x and an enterprise-value-to-sales ratio of 4x. Rewind to the tech bubble's zenith around the turn of the century, and the biggest players sported a P/E of 52x with an EV/Sales that soared above 8x. Even in the “nifty 50” bubble of the late 1960s, leading companies had a P/E above 34x.

Today’s big tech leaders aren’t as expensive as those in previous bubbles. Source: Goldman Sachs.

Many companies still have to benefit

A key driver of these elevated valuations is a small group of particularly early winners. While the near-term likely beneficiaries of AI have gained strongly this year, the longer-term likely beneficiaries haven’t. In previous bubbles, speculation spread out to a much wider range of companies and sectors. So far, we haven’t seen that.

Unlike near-term AI beneficiaries (dark blue line), likely longer-term winners (light blue) haven’t gained that much. Source: Goldman Sachs.

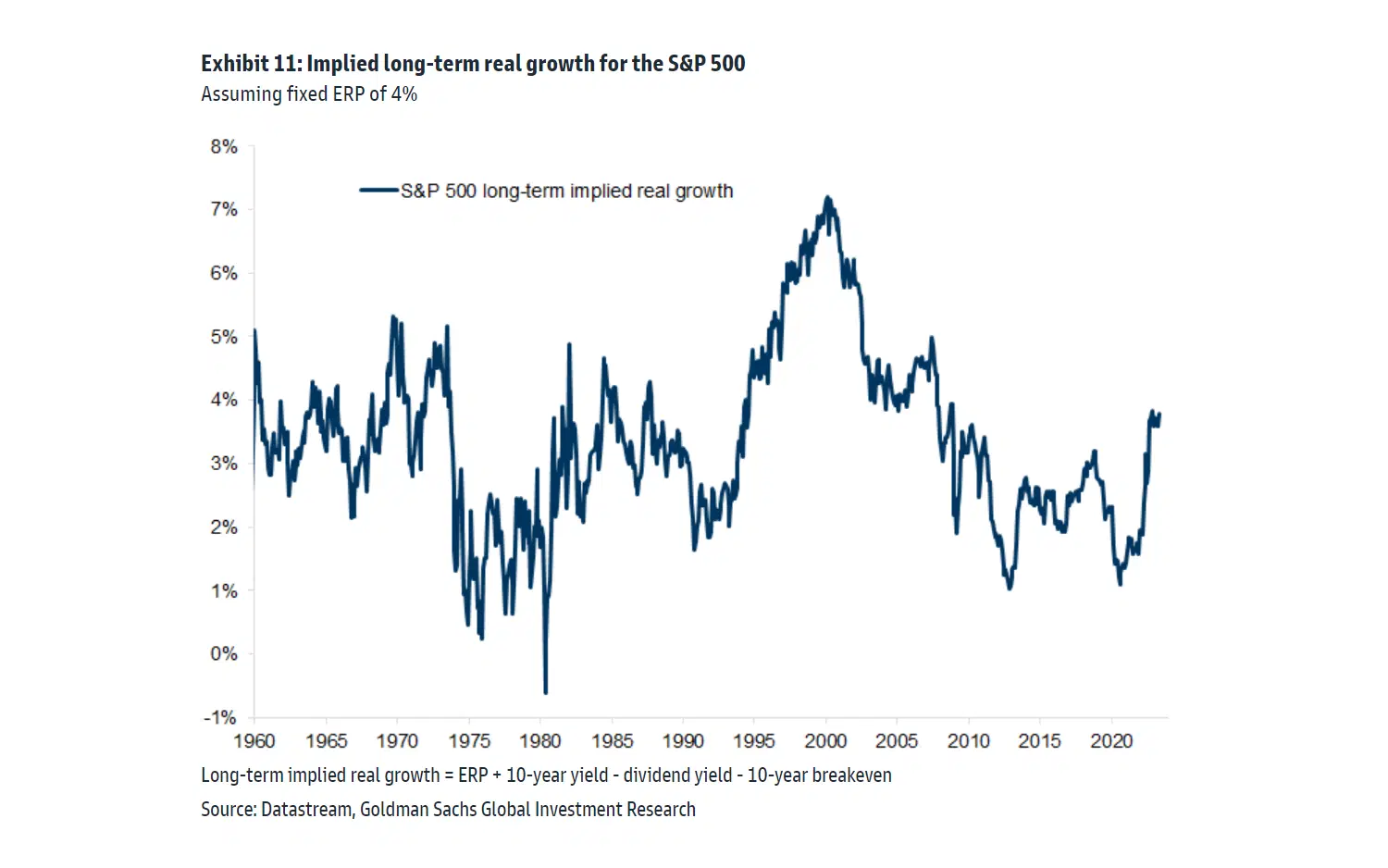

Long-term implied real future growth is reasonable

During a bubble, investors tend to have unrealistic expectations about long-term future real growth. And a good way to tell what the market actually expects is to assume an equity risk premium (the return investors need to see to invest in riskier stocks, rather than risk-free bonds), add the difference between the ten-year bond yield and stocks’ dividend yield, and subtract what inflation’s likely to be in ten years (through the 10-year breakeven rate).

Goldman crunched those numbers and calculated that while long-term growth expectations have jumped higher recently, they’re still not at levels we’ve seen in past bubbles, like the 1990s dot-com boom.

Investors’ expectations of long-term real growth have risen, but still look reasonable. Source: Goldman Sachs.

Relative to bonds and cash, tech isn’t outrageously expensive

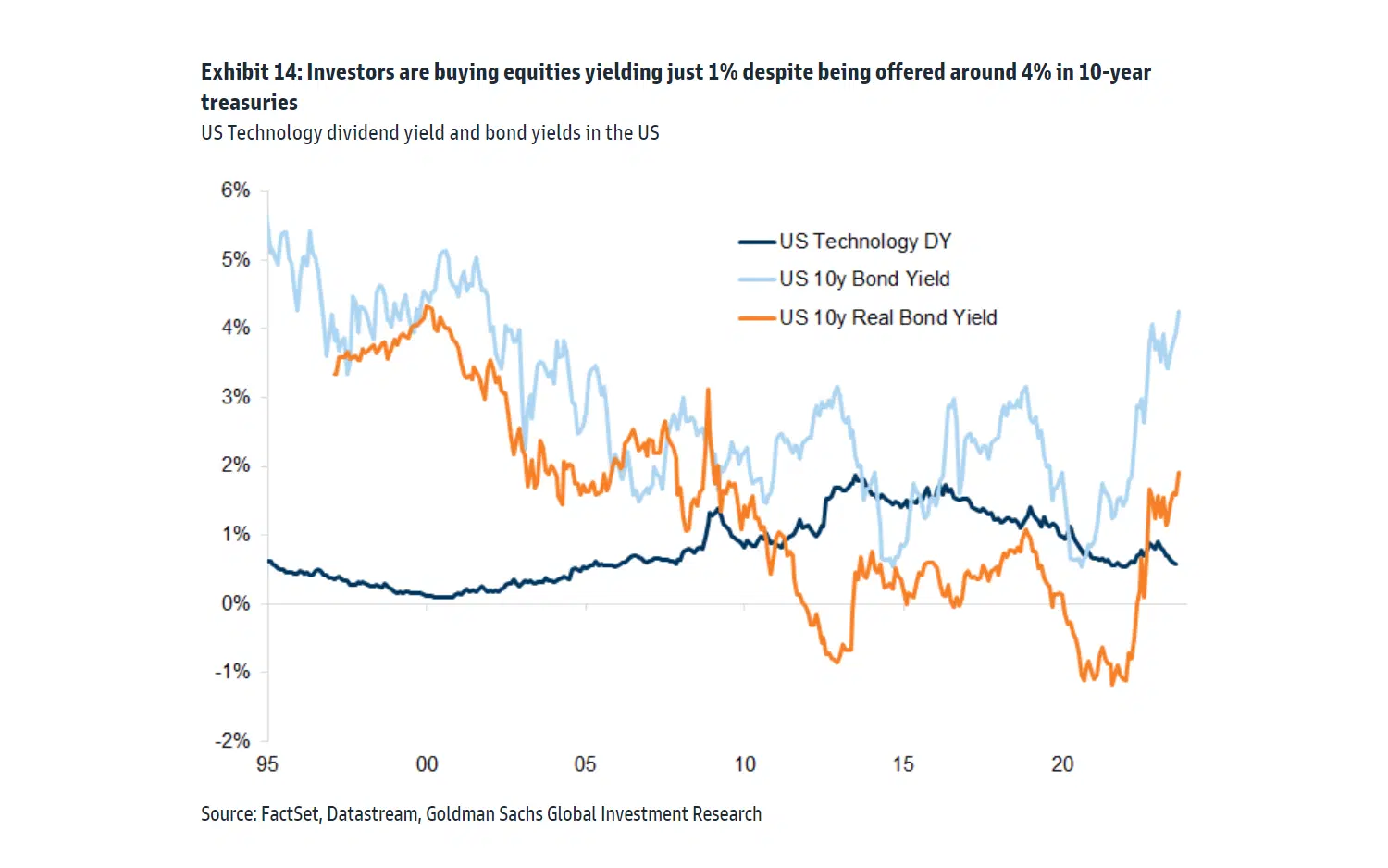

At the height of the dot-com bubble, investors were giving up a bond yield of close to 5% – roughly 4% after taking inflation into account – to buy stocks offering virtually no yield at all. That’s because they strongly believed that stock prices of tech companies would more than offset the difference in yield, even after adjusting for the higher risk. And sure, bond yields are once again higher than tech stocks’ dividend yields. But the difference today is much smaller: tech stocks deliver a dividend yield of about 1%, while (after adjusting for inflation) bonds offer just 2%.

The difference between US tech stocks’ dividend yield (dark blue line) and bond yields after adjusting for inflation (orange) has widened, but not massively. Source: Goldman Sachs.

So what’s the opportunity here?

Goldman’s argument – that AI is still far from bubble terrain – is hard to ignore. And if you agree with its findings, you’ll want to find the best ways to invest in AI. Here are two possible paths you might take:

Dive into established tech giants. The companies spearheading the AI movement and actively integrating AI into their operations have already seen big gains in their stock prices. And, look, they are bound to face some stiff competition as more firms crowd into the space, but Goldman says these tech behemoths are likely to hold the line longer than previous tech leaders. And that’s because tech is inherently deflationary, which deters political interference. And it’s because tech is vital for national infrastructure and defense. And it's because these tech companies’ huge cash reserves empower them to invest heavily in R&D, fortifying their competitive edge. So, given that, you might want to spread your investment across:

Enablers: companies like Nvidia that provide essential AI hardware.

Hyperscalers: like Microsoft ,Alphabet, and Amazon that scale up AI solutions.

Empowered users: such as Meta, Salesforce, and Adobe that harness AI to augment their offerings.

Bet on emerging stars. AI’s huge benefits will eventually trickle down to companies that leverage it to boost productivity, improving their revenues and potentially enhancing their margins. To pinpoint potential long-term beneficiaries, Goldman assesses not only the proportion of a company's wages that are vulnerable to AI, but also their sensitivity to labor costs. Merging these metrics helps project the potential boost in earnings.

On an industry basis, software and services, consumer staples distribution, and commercial and professional services could witness the most significant earnings surge from AI-driven labor productivity. On an individual company level, firms like Pinterest, Tenet Healthcare, DaVita, Clarivate, Robert Half, Guidewire, Alteryx, and Jones Lang LaSalle all showed promising prospects of doubling their long-term earnings in Goldman's earlier analysis this year.