Sometimes you have to take on the big questions. Could the enormity of the Magnificent Seven tech companies actually stand in the way of their stocks’ growth?

The stock prices of these seven big firms are assuming around 15% profit growth on average for the next ten years, which would boost S&P earnings growth from around 7% to 9% over that period.

That S&P 500 profit growth would take profit as a percentage of the overall economy to levels never seen before but, the non-corporate-profit part of the economy could still grow, so that doesn’t seem unreasonable.

Here’s the thing.

Logic says that these huge firms can’t continue to grow at their juiced-up pace forever. Mathematically, it’s not possible: a firm can’t grow faster than the overall economy year after year (at some point, it would just become the economy). And we do worry about that “forever” question.

If forever feels too abstract, let’s zero in on the next ten years. Could size itself restrict these firms from growing profit at outsized rates over the next decade, given they’re already so big? Now, some people refer to this matter as “the law of large numbers”. The law of large numbers states that when the number of independent samples grows big enough, the average of those samples converges on the actual, true mean. And that has nothing to do with this question. Those are two very different things.

Let's break this down.

There are three parts here. First is: what sort of growth rates does the market expect from these heavyweights to begin with – i.e. what’s priced in here? Second, then, is whether those growth rates are plausible, given these heavies already command a massive share of the S&P 500. In other words, if they grow at those priced-in levels, would that inflate the growth rate of the whole S&P 500 to unreasonable levels? And third, with these companies contributing ever-higher amounts to the market’s profit growth, does that level of S&P 500 profit look unrealistic when stacked against the overall economy?

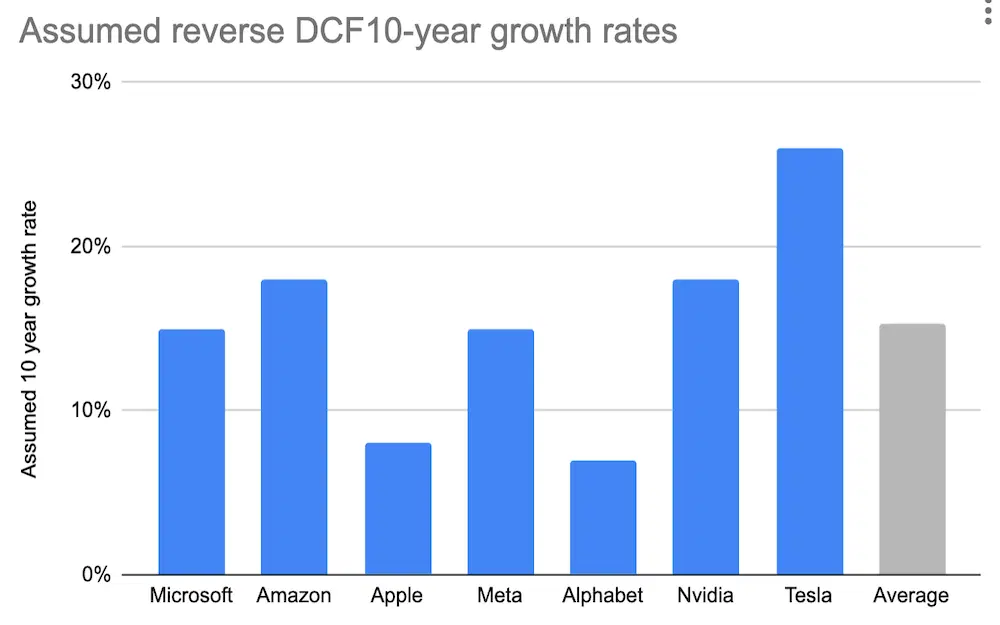

First up, the market is expecting 15% profit (or cash flow) growth over the next ten years for the seven biggest firms in the S&P 500 – a.k.a. the Magnificent Seven: Microsoft, Nvidia, Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, and Tesla.

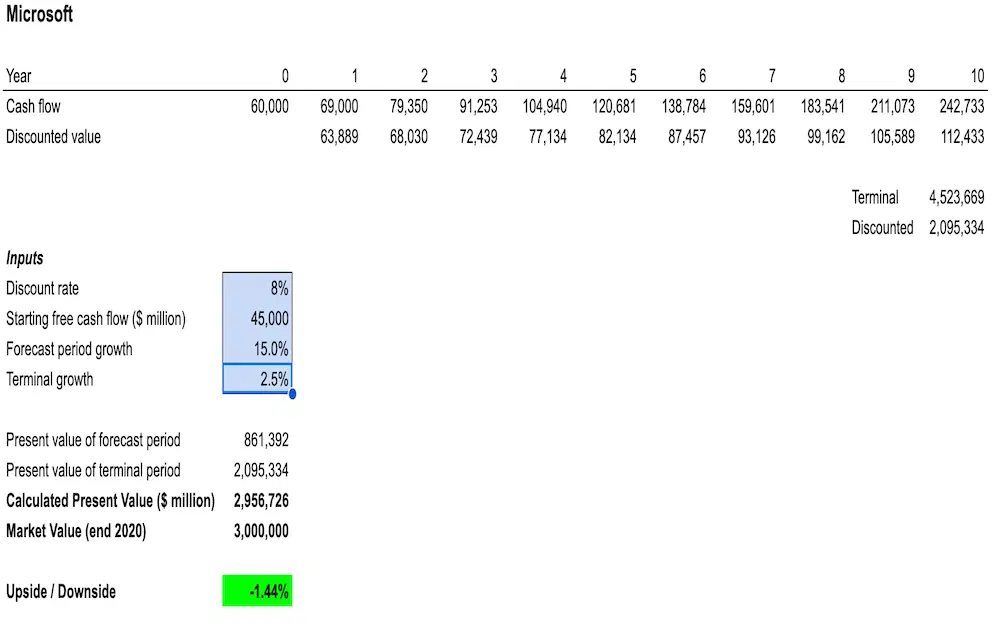

Discounted Cash Flow example. Microsoft’s company value is discounting 15% cash flow growth for the next ten years. Source: Koyfin.

The profit growth rate that’s “priced in” for the Magnificent Seven firms using my reverse DCF analysis. Sources: Finimize, Koyfin.

Next up, is whether these growth rates would have so much of an impact on the overall S&P 500 that it would make the profit growth numbers ridiculous. In other words, given the size of these firms, is 15% growth on average just too much to ask for – and does it distort the index growth to levels that just don’t seem possible?

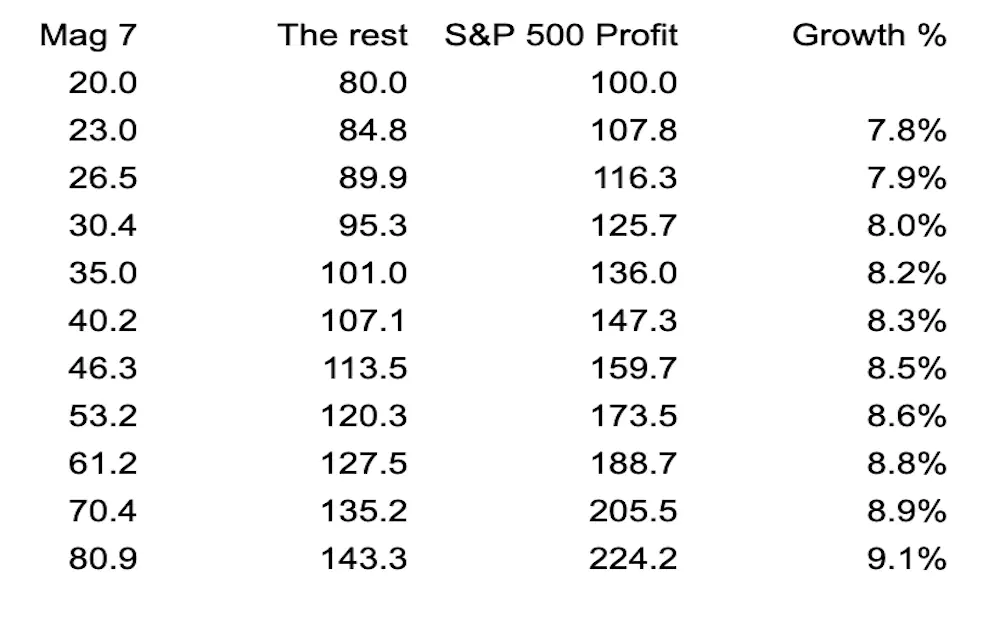

Take a look at this next table. It shows what happens to the profit of the overall S&P 500, assuming that these seven firms make up 20% of the S&P 500’s total profit.

An illustrative example of S&P 500 profit growth, assuming a profit split between the Mag 7 and the rest, and 15% growth for the Mag 7 and 6% for the rest. Source: Finimize.

What we've done here is assume the index starts with $100 in profit, $20 (or 20%) of which comes from the Mag 7 and $80 from the rest. This is a bit of a guess, to be honest. The Mag 7 firms make up 27% of the index by size, or market cap. Now that’s not the same as a profit split, because a company’s size (or market value) is as much about its valuation multiple as it is about raw profit. But, knowing that most of these firms are more expensive than the overall market, I can take a wild guess at what proportion of profit they make. So we're going for 20%. From there, mapped out what happens if that 20% grows at the 15% we calculated, while the rest of the index grows at 6%. (That 6% is also a guess, but conventional wisdom is that the S&P 500 isn’t likely to post the 8%-a-year profit growth that it’s been used to over the past half-century. So, yeah, 6% is a finger in the air, but it feels about right.

Anyway, look at the last column in the table: see, it’s starting at 7.8% and gradually creeping higher so that in ten years, the S&P 500 is growing at 9.1%. Now, our conclusion is that these numbers might look a bit optimistic, but they’re not unreasonable. The S&P has done better than that over the past ten years, after all.

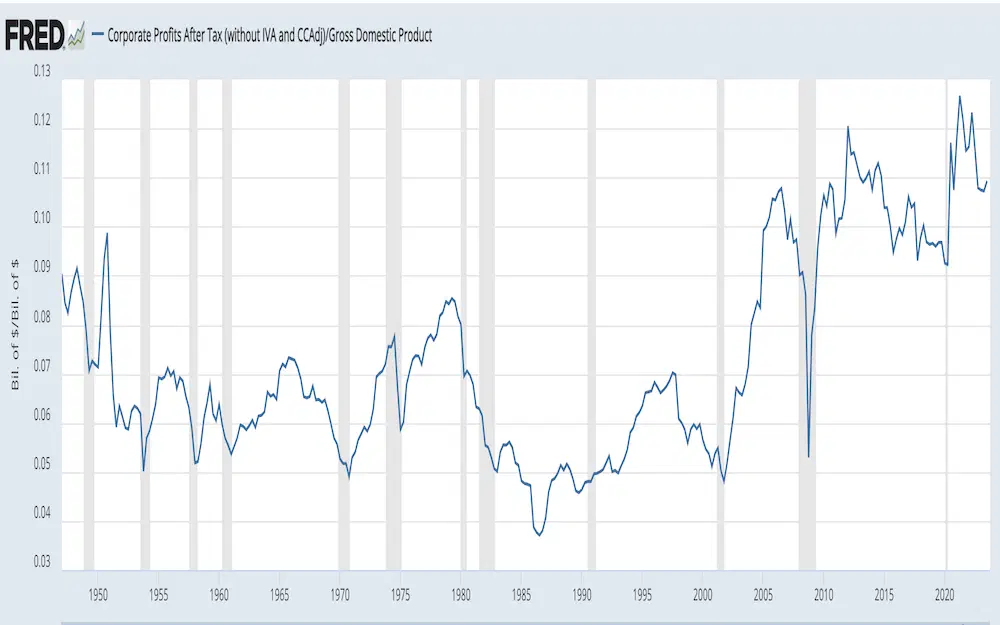

Finally, we need to make sure that this level of S&P 500 profit growth isn’t completely out of whack with reality. Again, this is all a bit of guesswork and there are a few ways to figure it. One is to consider how much corporate profits exist in the overall economy and to think about whether they can continue taking a bigger share of the pie – or whether they might reach their limit. That’s what this next chart shows, corporate profits as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), which is a broad measure of the overall economy.

US corporate profits as a percentage of US gross domestic product. Source: St. Louis Fed.

Right now, those profits are about 10%. And that’s close to the top of the past 70-odd years. Now, while we don't have a solid reason why it shouldn’t be more, it’s a mathematical fact that if profit continues to grow faster than the economy, and takes more of the pie, at some point economic growth has to accelerate, or the non-corporate-profit part of the economy has to begin declining. And if that happens, well, that could be a whole thing – the start of a crisis, perhaps.

But, that’s all hypothetical, because for the next ten years, S&P 500 profits can tick higher at the rates I’m assuming and the non-corporate-profit part can still grow, even while the overall economy expands at just 3%. The next chart shows how this would work.

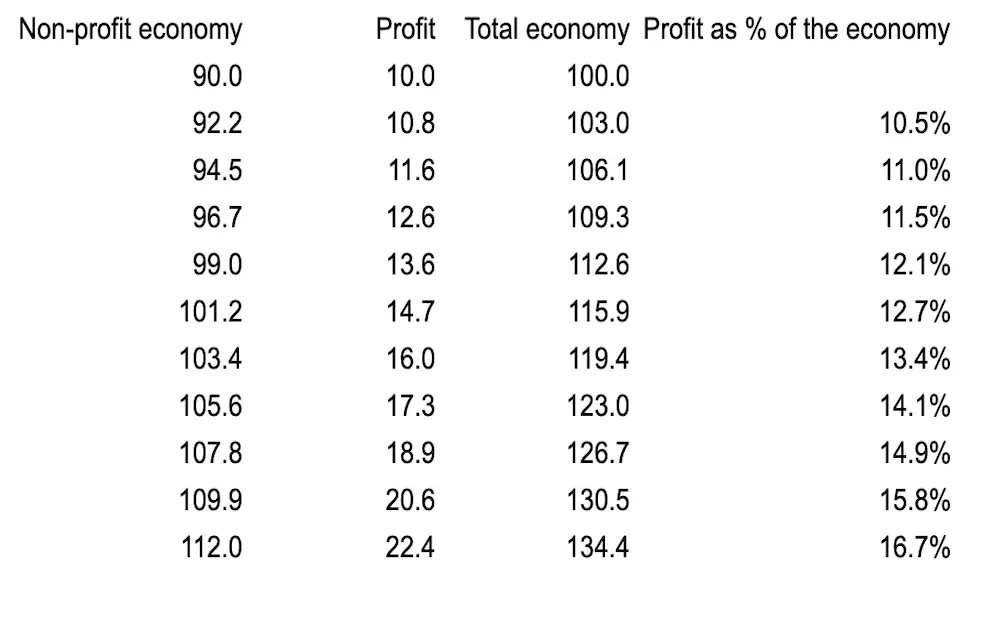

Table showing what happens to the non-corporate-profit part of the economy – it still grows – if the overall economy grows at 3%, and profit grows at the assumed rates calculated. Source: Finimize.

Here, calculations were similar to the ones we did before, but instead of the 80/20 split with the Mag 7 and the non-Mag-7, I’ve done a 90/10 split with profits making up 10% of the economy and all other things (all other goods and services produced, generally) accounting for 90%. This time, we've grown that corporate profit at the rates we calculated above and assumed the overall economy (in the third column) grows at a constant 3% – a reasonable long-term assumption.

The conclusion here is that with the assumed profit growth, and a fixed 3% economic growth, the rest of the economy can still grow for the next ten years, albeit by a decreasing amount. You can see that in the first column. At the end of ten years, corporate profit would make up nearly 17% of the overall economy. That’s more than ever, and that stat alone would get some people saying that none of this is possible. There is no reason to argue that corporate profits can’t go that high. If – with the fixed 3% overall economic growth – that meant the rest of the economy would be declining, we might think differently. But these rough calculations show that wouldn’t have to be the case.

Now, the big takeaway.

So what can you make of all this? Well, hopefully, you’ve followed the logic at least. Admittedly, we don’t have any eureka moments here, but came away feeling a heck of a lot better about the prospects of the Mag 7 growing by 15% on average for the next ten years, and believing that size alone shouldn’t stand in the way of that. Of course, that doesn’t mean the share prices will go up. After all, 15% on average is what’s priced in now. In theory, to do better than that, they’d need to grow even faster (or you’d have to wait for a cheaper entry price to make money). But it does mean that those profit assumptions are not outside the realm of possibility and that there’s no immediate size impediment.

-

Capital at risk. Our analyst insights are for information purposes only.