US electricity demand has been, ahem, static over much of the past two decades, but it’s finally beginning to light up. That’s partly thanks to the explosive growth of AI. The innovative technology’s huge need for power now means that utility companies – traditionally one of the dullest corners of the stock market – could offer investors a pretty exciting way to play the market’s latest obsession. I’ve taken a look across the industry and found three standout firms.

Thesis

Utilities are heavily regulated businesses that are permitted to earn a specified return on their “rate base”, which is essentially the total value of their approved investments. Because of this mechanism, a utility’s profit growth is mainly determined by its rate base growth.

Power demand is forecast to grow by 55% between 2020 and 2040 in the US, with data centers accounting for roughly half of the expansion. That’s six times the 9% increase seen between 2000 and 2020.

To meet this huge, once-in-a-generation surge in power demand, US utilities will have to invest heavily in new generation and transmission capacity. That, combined with the need to replace aging grid infrastructure and transition from coal to cleaner energy, will drive a structural shift in the size of US utilities’ investments and, in turn, the pace of their rate base growth.

That makes utility stocks a potentially attractive investment. First, the sector's valuations are attractive relative to the broader market, especially given its ability to deliver solid total investor returns with much greater visibility and predictability than other industries. Second, falling interest rates (the environment we’re in today) tend to benefit utility stocks disproportionately. Third, having these shares in your portfolio can be a good way to increase diversification and protect against rough patches.

And, sure, it’s perfectly sensible to use an ETF to gain broad exposure to the sector. But if you want to make a more calculated wager, three utilities stand out: Dominion, NextEra, and Constellation.

Dominion serves Northern Virginia – the biggest data center market in the US by a mile. The utility is investing heavily to meet the region's growing power demand, which is projected to double by 2039 – dwarfing the 55% increase expected for the US as a whole.

NextEra is America’s biggest developer and operator of wind and solar farms, capitalizing on a huge surge in renewable energy projects. The firm also owns a well-managed regulated utility operating in one of the fastest-growing states.

Constellation is the country’s biggest owner of nuclear power plants, which are now in high demand from deep-pocketed tech firms trying to meet the massive energy needs of their data centers while staying aligned with their climate commitments.

Risks

Sector-wide threats include rising bond yields, potential regulatory pushback on utilities’ big investment plans, increasing financing requirements, and the possibility that lofty power demand growth forecasts may prove overly optimistic.

Dominion faces some big-project uncertainties related to the huge offshore wind farm it’s building.

NextEra’s risks include regulatory uncertainty over its utility’s investment plan and potential changes to green energy tax credits. (Any repeal or watering down of these tax credits could also hurt Constellation’s nuclear business.)

Other risks for Constellation include the potential for falling power prices and a bumpy, costly integration of Calpine (a rival that Constellation has agreed to buy).

PART I: HOW THE UTILITIES SECTOR WORKS

Utilities are heavily regulated businesses that are permitted to earn a specified return on their “rate base”, which is essentially the total value of their approved investments. Because of this setup, a utility’s profit growth is determined mainly by its rate base growth.

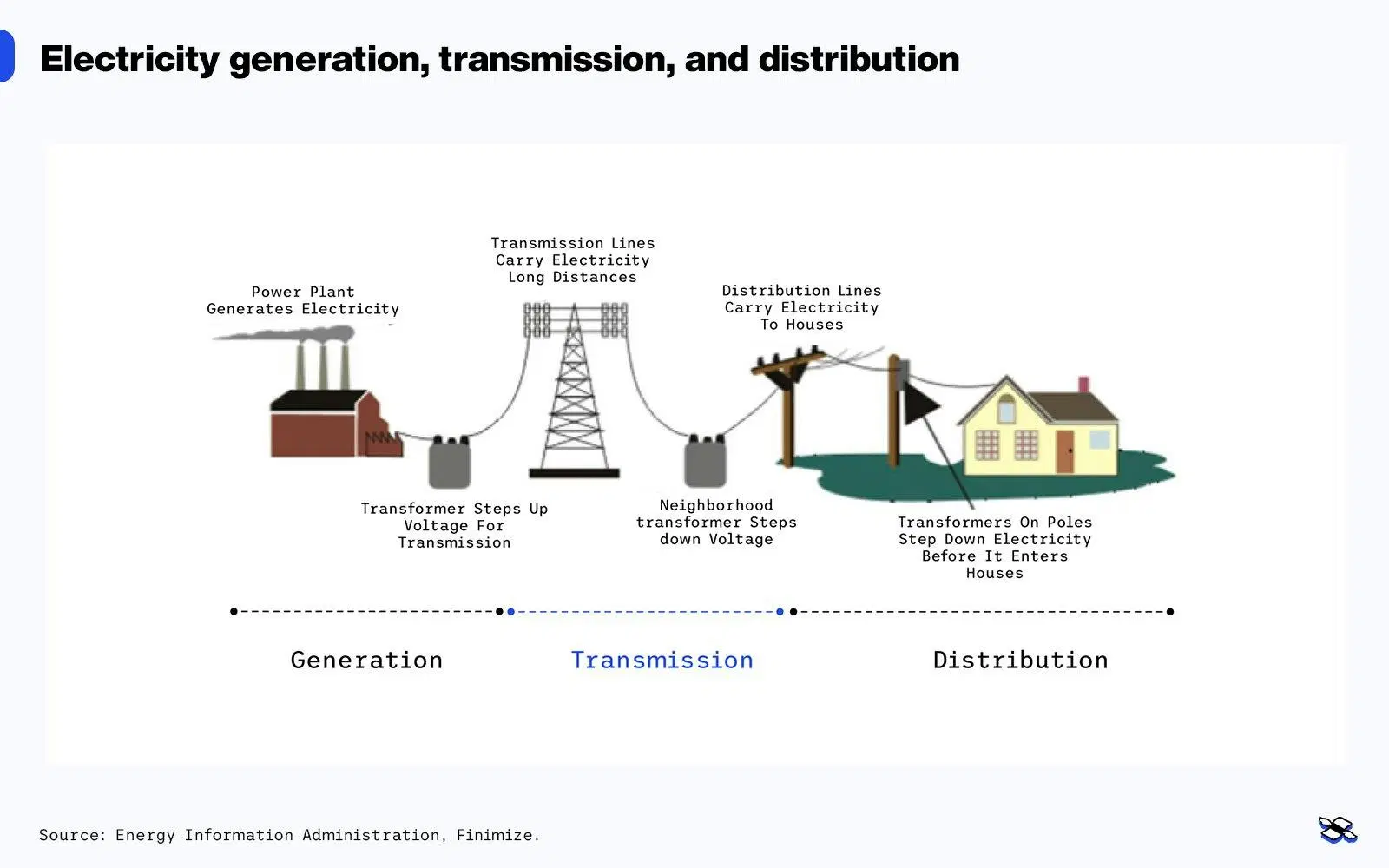

There are three main types of utility firms, each characterized by what they provide customers: electricity, gas, or water. Electric utilities – the focus of this research piece – do two things: 1) generate power, and 2) transmit and distribute power. Generation is pretty self-explanatory (think power plants, wind farms, and so on). Transmission and distribution, meanwhile, is the process of getting that generated energy to homes or businesses. An electric utility may do one or both of these things (firms in the latter group are known as “vertically integrated utilities” because they control the entire value chain, from spark to socket).

The transmission and distribution trade is a natural monopoly. In other words, a single utility firm typically owns and operates the entire infrastructure in any given area, with few worries about competitors muscling in on its turf. That’s because it makes little sense to have multiple (very expensive) power lines running alongside each other. Similarly, only a few US states have competitive energy markets, and as a result, the business of generating electricity is also a natural monopoly in most parts of the country.

Electricity generation, transmission, and distribution. Sources: Energy Information Administration, Finimize.

Now, because utilities often have the exclusive right to operate in a particular area, they’re generally heavily regulated to ensure that customers get fair pricing and good service. So government authorities typically have the final say on what companies can spend, what they can charge customers, and, therefore, what returns they can make – among other things.

The precise nature of this regulation differs from one state to another. But one thing that’s common everywhere is the concept of “rate base” – one of the most important metrics for utility companies (and, therefore, their investors).

Rate base is essentially the value of a utility’s combined investments – in power plants, transmission lines, distribution networks, EV charging stations, and so on. It rises when the utility spends money on infrastructure, but it also falls a bit every year because of depreciation.

Rate base is the most important factor in determining a utility firm’s profit because it’s what regulators allow utilities to earn a return on. Imagine, for example, that a utility spends $200 million to build a new power plant, financed using a 50/50 mix of debt (bonds and loans) and equity (stocks). That new plant will increase the utility’s rate base by $200 million. Now, suppose the regulator allows the utility to earn a 10% return on equity (ROE). In that case, the new plant would increase the utility’s profit in year one by $200 million x 50% (the percent funded by equity) x 10% (the allowed ROE) = $10 million. (In reality, there could be other factors that affect the utility’s precise profit.)

Here’s the key takeaway: a utility’s profit growth is mainly determined by its rate base growth. That’s because the allowed ROE and debt-to-equity financing mix doesn’t change much from year to year, but a utility’s rate base does.

PART II: A ONCE-IN-A-GENERATION GROWTH OPPORTUNITY

When electricity demand is booming, utilities have to invest in new generation capacity, transmission lines, and other things. That increases their rate base and, in turn, their profits. So here’s the good news: power demand in the US is expected to soar in the coming decades, mostly because of AI’s explosive growth and all the data centers needed to make it run.

Global electricity demand is rocketing as the world builds more power-thirsty AI data centers, switches to EVs, uses more air conditioning, mines cryptocurrencies, and electrifies heavy industries like steel production and water desalination. In its latest outlook, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said the world is entering a new “age of electricity” and predicted that global power demand will double by 2050. Between 2023 and 2035 alone, demand is expected to grow by almost 1,000 terawatt hours a year – equivalent to adding the entire electricity consumption of Japan every 12 months.

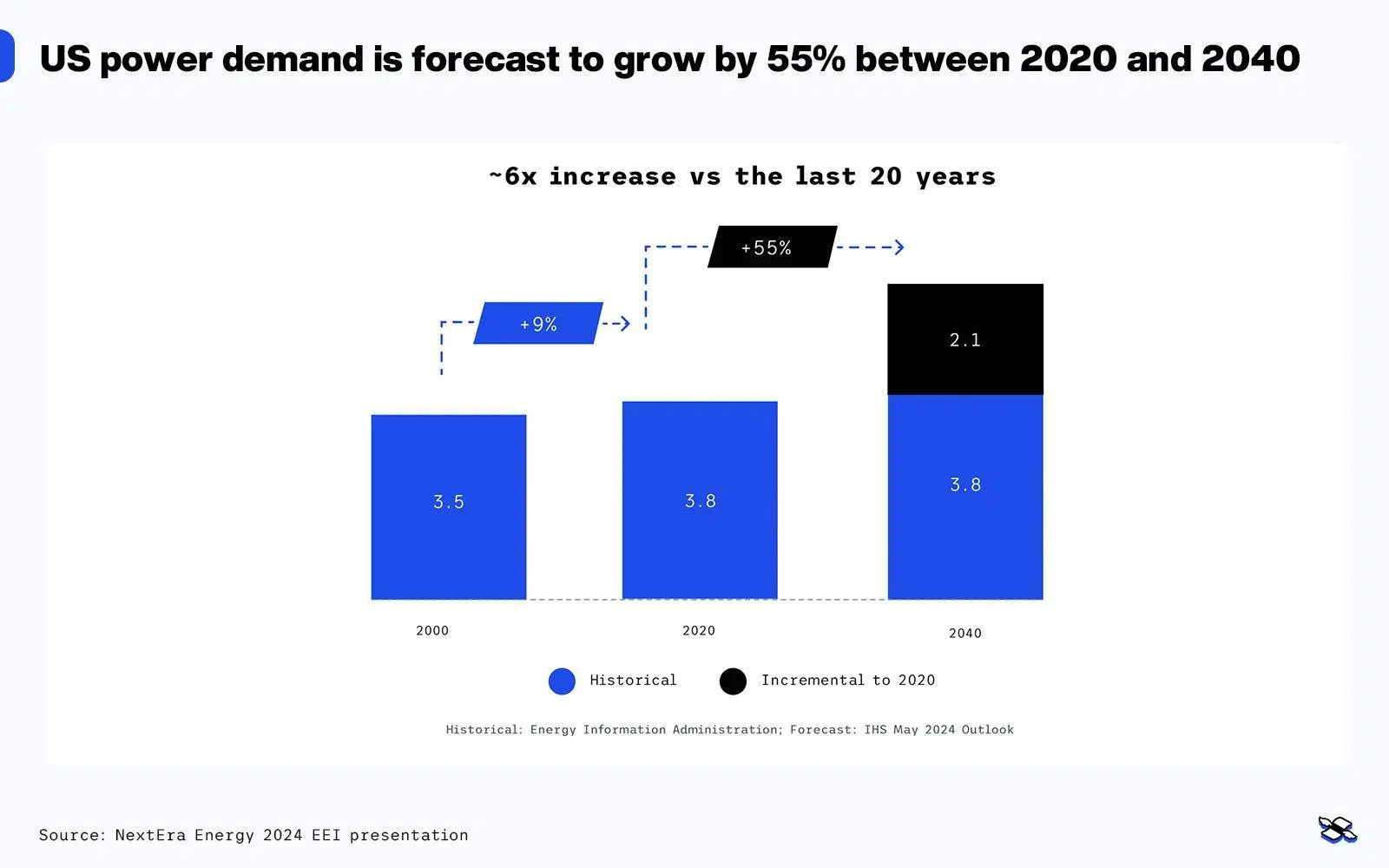

In the US alone, power demand is forecast to grow by 55% between 2020 and 2040, with data centers accounting for roughly half of the expansion. That’s six times the 9% increase seen between 2000 and 2020, when electricity demand growth was relatively anemic because of energy efficiency strides, slower economic growth, and the offshoring of some heavy industries.

US power demand is forecast to grow by 55% between 2020 and 2040. Source: NextEra Energy 2024 EEI presentation.

To meet this huge, once-in-a-generation surge in power demand, US utilities will have to invest heavily in new generation and transmission capacity. That – combined with the need to replace aging grid infrastructure and transition from coal to cleaner forms of energy – is expected to drive a structural shift in the size of US utilities’ investments and, in turn, the pace of their rate base growth. (Friendly reminder: a utility’s profit growth is mainly determined by rate base growth.)

PART III: MORE GOOD REASONS TO INVEST

The utilities sector's valuation is attractive relative to the broader market, especially given its ability to deliver solid total investor returns with much greater visibility and predictability than other industries. What’s more, falling interest rates (the environment we’re in today) often disproportionately benefit utility stocks. Finally, having these firms in your portfolio can be a good way to increase diversification and protect against rough patches.

Reason 1: The sector’s relative valuation is attractive.

The US utilities sector’s 12-month forward price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio stands at 17x – that’s about a fifth lower than the S&P 500’s valuation. And that’s pretty striking: for the past 20 years, this sector’s valuation has, on average, been right in line with the overall index. That current 20% discount seems unreasonable, in my opinion, when you consider that the sector’s growth prospects today are stronger than they’ve been in the past two decades.

The US utilities sector is trading at a 20% discount to the S&P 500, based on forward price-to-earnings ratios. Source: Finimize.

What’s more, utility firms’ forecasted earnings growth over the next five years – at roughly 6% to 8% a year – could match or even outpace that of the broader market (especially if you exclude the few tech firms that are disproportionately driving the S&P 500’s quick profit expansion). That’s not to mention the fact that the utilities sector’s earnings growth comes with a lower risk profile, thanks to the regulated nature of the industry, with highly predictable rate base growth driving the increase in earnings.

Reason 2: Falling interest rates could boost utilities’ stock prices.

Most of the world’s major central banks have been gradually cutting interest rates. Falling interest rates generally lead to lower bond yields, as existing bonds with higher rates become more attractive, driving up their price and reducing their yield. And that trend is typically good for utility investors.

See, because utility stocks pay out a chunky portion of their profits in dividends, investors sometimes think of them more like income-paying bonds. Utility stocks therefore tend to perform better when yields on corporate and government bonds are falling (and worse when bond yields are rising, making their dividends seem less attractive). Lower bond yields also lower a utility’s financing costs – which is important for a sector that relies heavily on debt to fund its huge investments.

Still, it's worth noting that bond yields in the US have actually been rising since September. That’s because investors have become increasingly concerned about persistent US inflation and the government’s growing debt pile, both of which have overshadowed the three interest rate cuts the Federal Reserve has made over the past few months. But if these worries ease, bond yields should – in theory – begin to decline again.

Reason 3: The sector offers an attractive total investor return with high visibility.

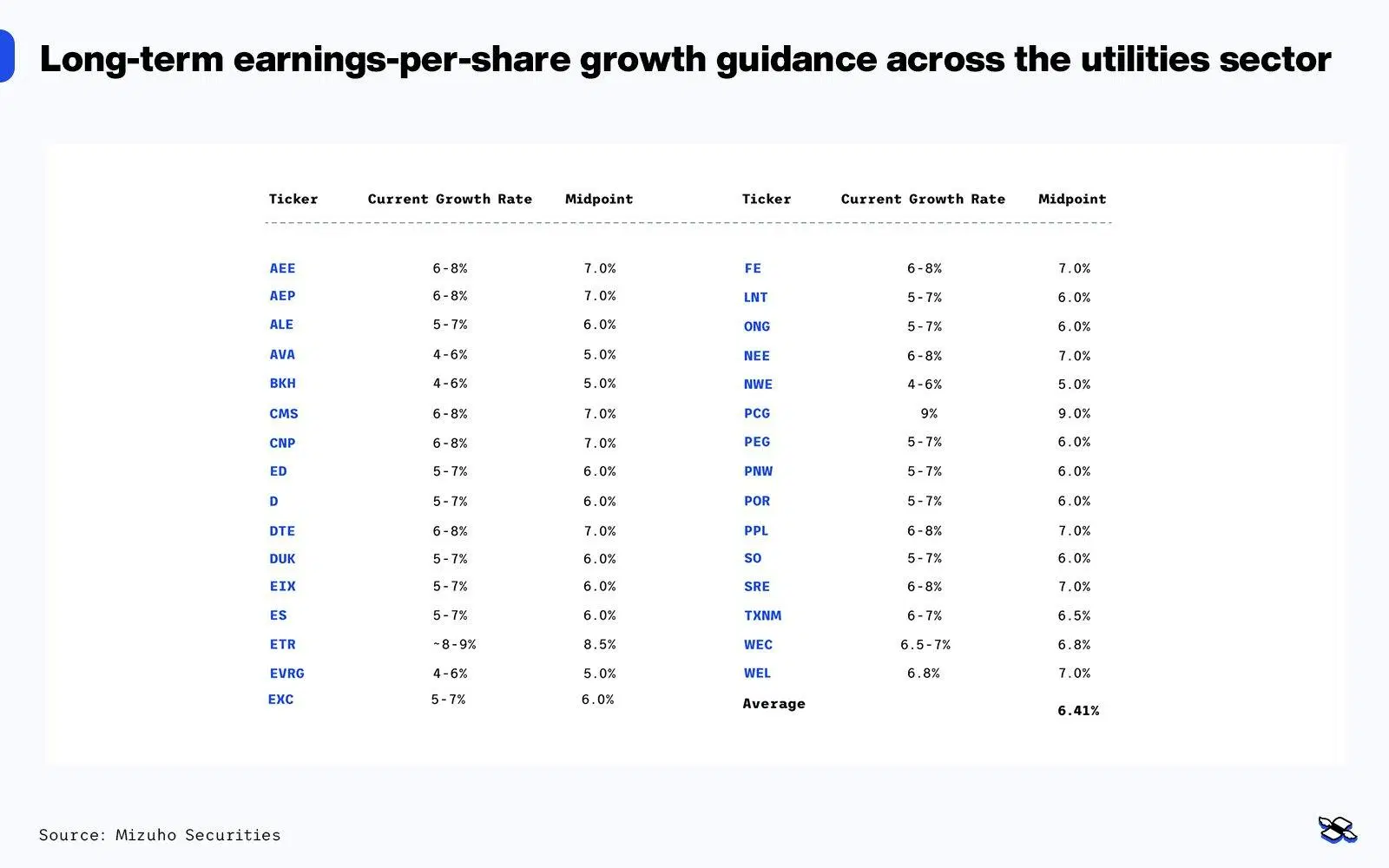

I mentioned earlier that utility firms’ forecasted earnings growth is expected to be around 6% to 8% annually over the next five years. And that’s not arbitrary – it’s the explicit profit guidance provided by the management teams of many utility firms, as shown below.

Long-term earnings-per-share growth guidance across the utilities sector. Source: Mizuho Securities.

Utility management teams are able to serve up extremely confident long-term earnings forecasts – and that boils down to the fact that a utility’s profit growth is driven by its rate base growth. Here’s how it works: a utility company typically maps out its infrastructure investments for the next three to seven years and submits the plan to regulators. After some back and forth, the plan gets approved (sometimes with modifications), providing the utility with a high level of visibility into its rate base growth for the years ahead.

In any given year, the utility’s rate base, allowed ROE, and debt-to-equity financing mix will determine its permitted profit. Approved expenses, from interest and tax to fuel and maintenance costs, are then added to calculate total permissible revenue. By dividing this revenue figure by the expected amount of power the utility will sell, the regulator can specify the allowable charge per unit of electricity – ensuring that the utility earns its approved sales and profit.

How a utility’s revenue and profit are determined by regulators. Source: Finimize.

It’s worth noting that a utility’s earnings growth might not perfectly match its rate base growth. In fact, it’s often slightly lower because many utilities issue new stocks to fund their investments, which dilutes their earnings per share (EPS). But that’s usually factored into management teams’ guidance.

The bottom line is that the regulated nature of the utility industry gives companies a high degree of future earnings predictability. As shown in the table earlier, firms in the sector are expected to grow their EPS by an average of around 6.5% per year. And this could go even higher as utilities bulk up their investment plans to meet surging power demand in the US. For example, in October last year, two firms – Entergy and Xcel Energy – raised their five-year EPS annual growth rates by two and one percentage points, respectively.

Now, assuming the sector’s EPS grows by 6.5% a year and its P/E ratio remains stable, then a stock price index tracking the industry could rise by a similar amount. Throw in a current dividend yield of 3.5%, and you could be looking at a roughly 10% annual total shareholder return over the next five years. Not many sectors can boast double-digit long-term annual returns with such high visibility.

Reason 4: Utility stocks could protect your portfolio against rough patches.

Utility stocks are famously “defensive” – known to stand their ground even during economic downturns. That’s because these companies provide essential everyday services like electricity and water. And while that means revenue and profits may not always grow very rapidly, they do tend to remain resilient when the going gets tough. It’s why utility stocks are less volatile than the overall stock market – and why their prices typically outperform when the broader market falls.

So having utility stocks in your portfolio can be a good way to increase diversification and protect against the market’s rough patches. And because they tend to pay a steadily growing dividend, they can also give you a reliable income stream to help offset losses elsewhere in your portfolio.

PART IV: STANDOUT UTILITY STOCKS

Here are three companies to put on your radar: Dominion Energy, NextEra Energy, and Constellation Energy. Dominion serves Northern Virginia – easily the biggest data center market in the US (and growing). NextEra, meanwhile, is America’s leading developer and operator of wind and solar farms. And Constellation is the country’s top owner of nuclear power plants.

I’m going to dive into each stock, but before I do, it's worth noting that gaining broad exposure to the sector through an ETF is a perfectly sensible approach. After all, the major trends are expected to benefit all firms in the industry to some degree or another. The biggest ETF that tracks the US sector is the Utilities Select Sector SPDR Fund (ticker: XLU; expense ratio: 0.09%). Or, if you’re outside the US, you could consider the iShares S&P 500 Utilities Sector UCITS ETF (IUUS; 0.15%). However, if you're looking to combine an investment in a utilities ETF with targeted bets on specific companies, three firms stand out to me.

Dominion Energy: the data center play.

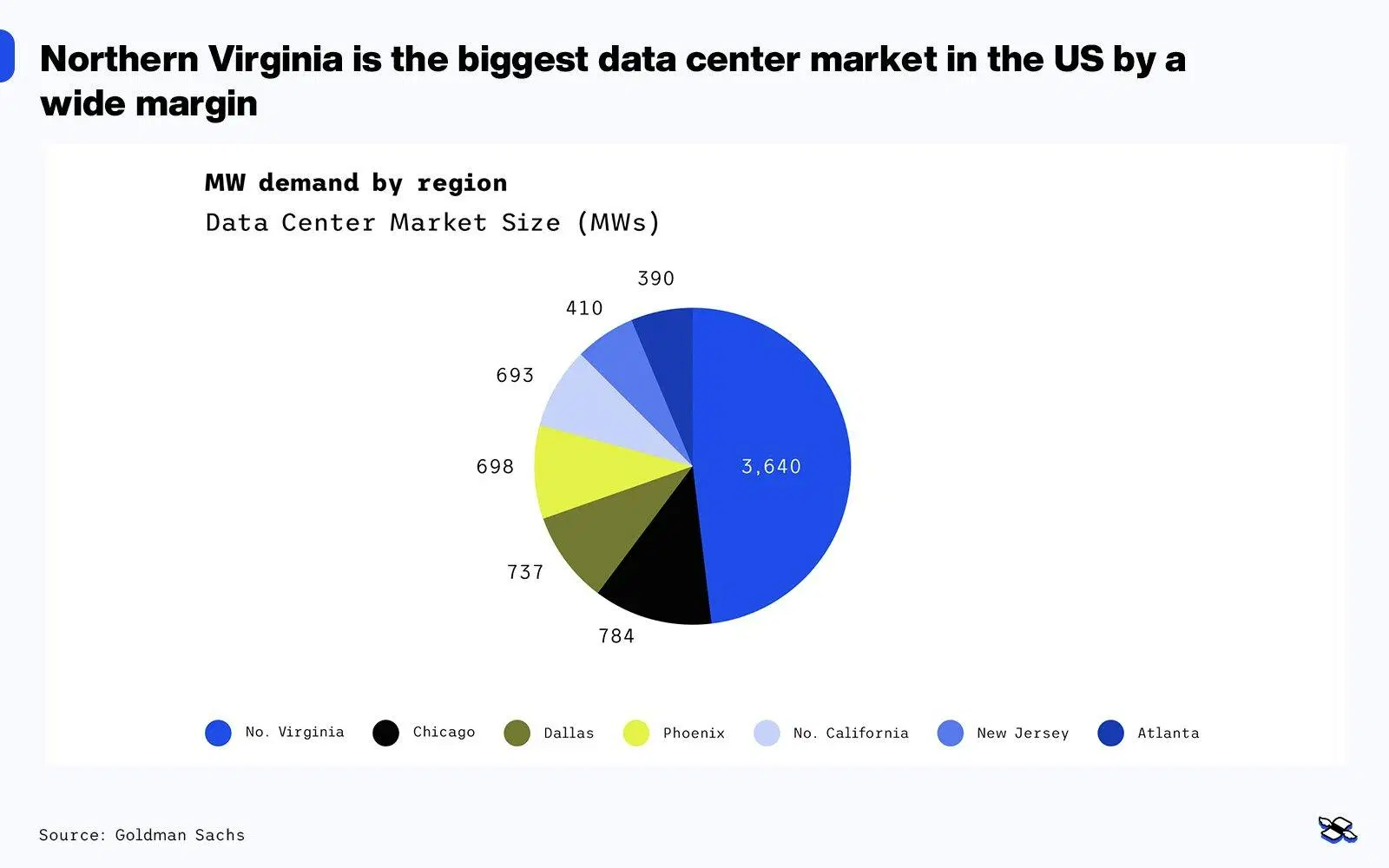

US data centers are clustered in Northern Virginia, Dallas, Silicon Valley, Phoenix, Chicago, Atlanta, Portland, Seattle, Los Angeles, and the New York/New Jersey area. Northern Virginia has by far the most, with more data centers than the next five areas combined. And it’s easy to see how it became a favored destination: it’s got cheap electricity, access to major underwater fiber cables, a big technical workforce, and generous state tax incentives.

Northern Virginia is the biggest data center market in the US by a wide margin. Source: Goldman Sachs.

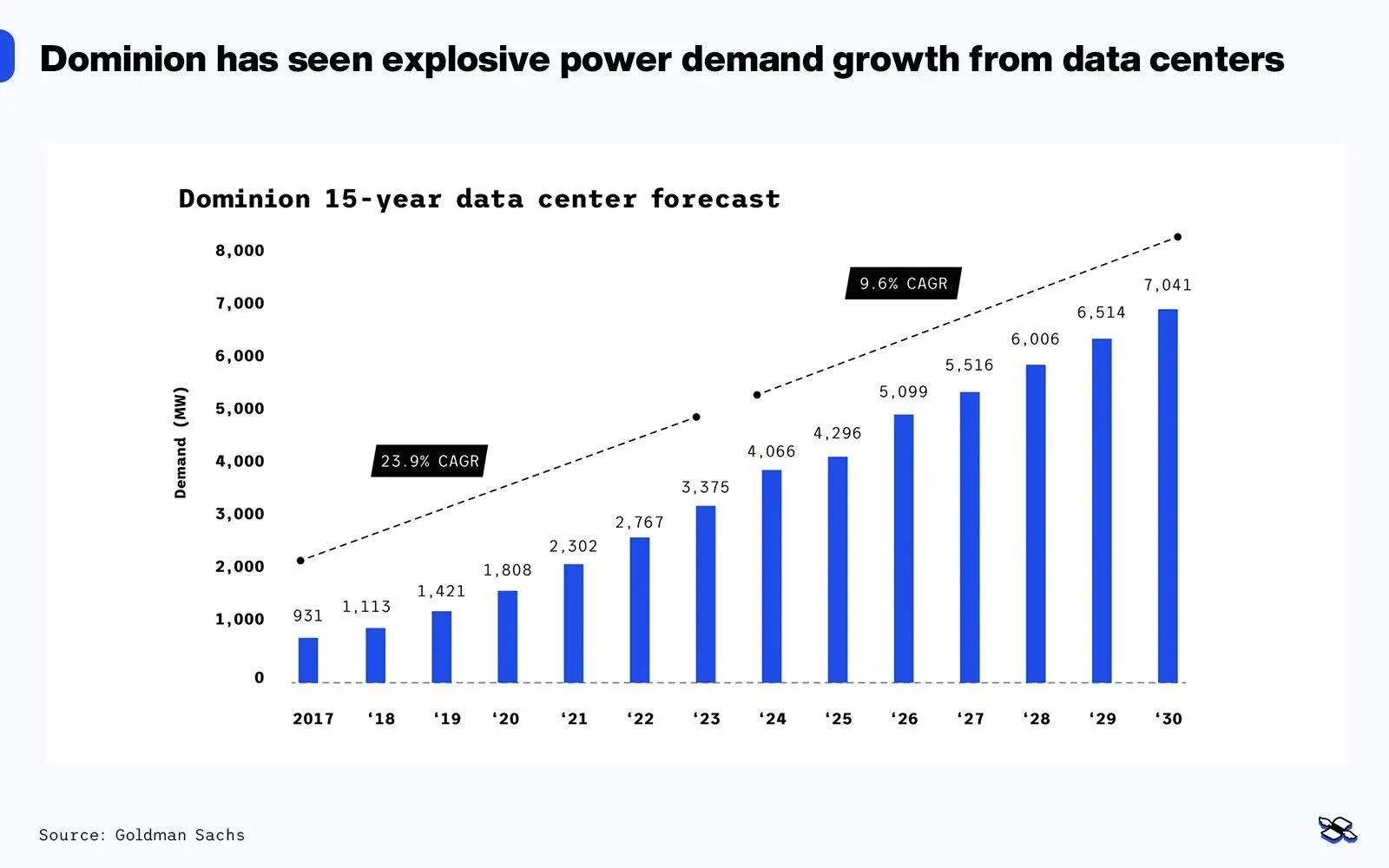

The main electric utility serving Northern Virginia is Dominion Energy Virginia (DEV), owned by the listed firm Dominion Energy. To see how good the data center boom has been for the company, consider this: power demand from data centers in its service territory grew at a nearly 24% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) from 2017 to 2023 and is forecast to expand at a 9.6% CAGR through 2030. Combined with growing electricity consumption from other industries, Dominion projects that its total power demand will double by 2039 – dwarfing the 55% increase expected for the US as a whole.

Dominion has seen explosive power demand growth from data centers. Source: Goldman Sachs.

But, remember, power demand growth only results in higher earnings if it leads to rate base growth. DEV is investing $35.5 billion over the next five years to expand and enhance its infrastructure. As a result, it expects its rate base to rise at a 9% CAGR over that time. However, because Dominion owns a utility in South Carolina that isn’t expanding as fast, the firm’s overall rate base growth is expected to be just 7.5% (which, in fairness, is still quite high compared to other utilities).

As a result, Dominion expects its EPS to rise at an annual rate of 5% to 7% over the next five years. And, yes, that’s slightly lower than its forecasted rate base growth, but that’s because the firm plans to issue $3.5 billion worth of new stock over the period to fund its investments, and the increase in shares outstanding will naturally dilute EPS.

If EPS increases at the midpoint of the expected range (6%) and Dominion’s P/E ratio remains stable (it’s currently 15.8x, based on forecasted profits over the next 12 months), then its stock price could rise by a similar amount. Throw in its current 5% dividend yield, and you could be looking at a roughly 11% annual total shareholder return over the next five years. This could increase further if Dominion’s P/E ratio, which is currently 7% below the sector average, rises to match or exceed the industry average.

NextEra Energy – the renewables play.

NextEra Energy owns two businesses:

Florida Power & Light (FPL) – a spark-to-socket vertically integrated regulated utility in Florida, and one of the biggest utilities in the nation. The segment accounts for roughly 60% of NextEra’s total earnings.

NextEra Energy Resources (NEER) – the top developer and operator of renewable energy projects in the US. Its huge portfolio makes it the world's leading wind and solar energy generator. The segment accounts for roughly 40% of NextEra’s total earnings.

FPL is a very well-managed utility operating in one of the fastest-growing states, with a long record of delivering power to customers at much lower costs than the national average. Its latest investment plan, approved by regulators in 2021, is set to drive a 9% CAGR in its rate base between 2021 and 2027. That’s much higher than other utilities. Now, FPL is poised to file another multiyear investment plan with regulators this year, which could see the utility extend its strong rate base growth through the end of the decade. That’s because it’s spending heavily to meet rising power demand, decarbonize its generation mix, strengthen its grid against Florida's frequent storms, and more.

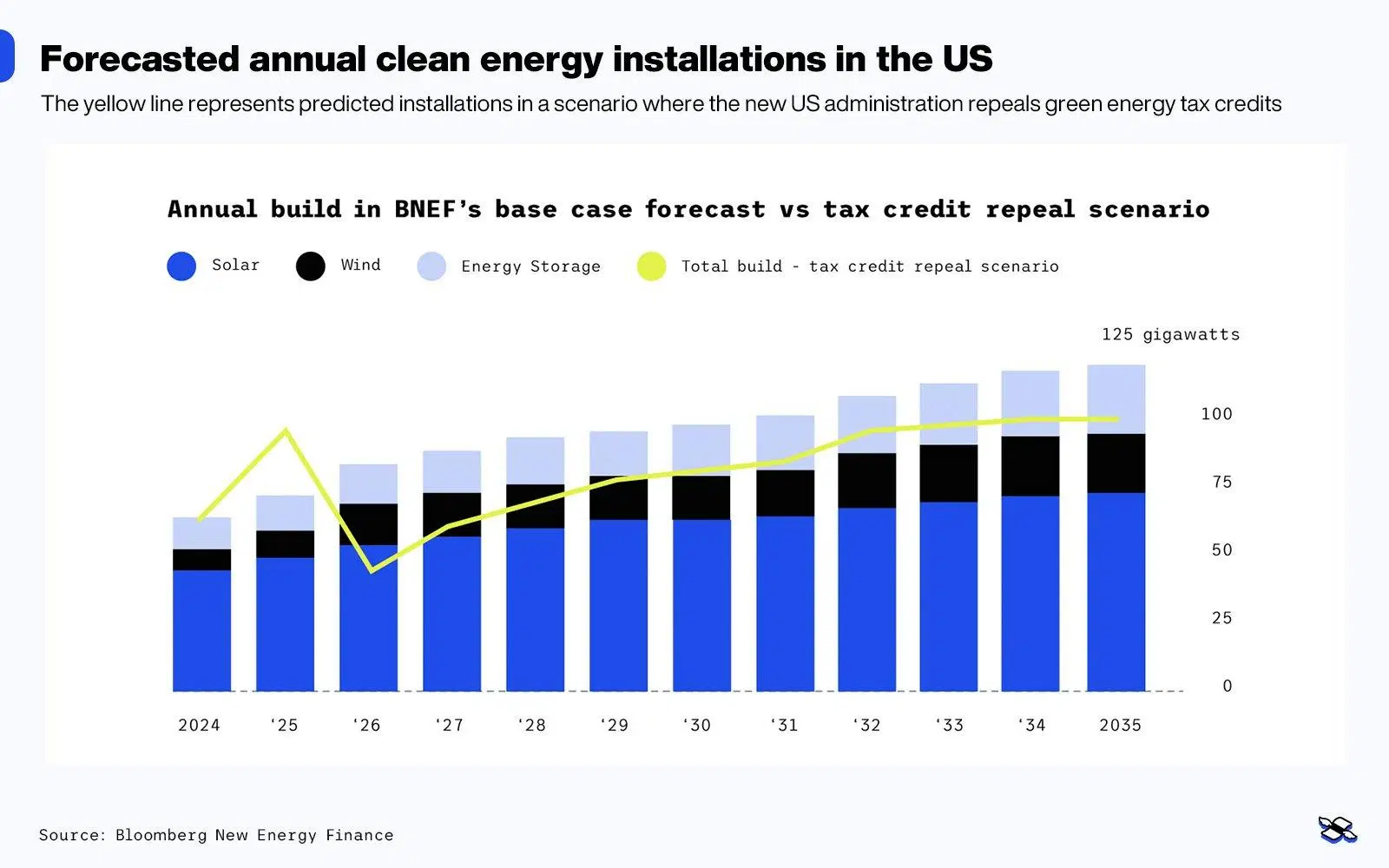

As for NEER, it’s a key enabler of one of the industry’s biggest trends: the transition away from traditional fossil-fuel power generation (like coal) and toward renewable energy (like wind and solar). Renewable energy is currently the fastest-growing source of power in the world, driven by its cost competitiveness and supportive government policies. Bloomberg New Energy Finance, for example, forecasts annual wind, solar, and battery storage installations in the US will average 102 gigawatts (GW) over the next 11 years – quadruple the amount over the past 11 years.

Forecasted annual clean energy installations in the US. The yellow line represents predicted installations in a scenario where the new US administration repeals green energy tax credits. Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

That big jump in installations is set to benefit NEER, which develops one in every five renewable energy projects in the US. The firm operates virtually all the wind and solar farms it builds, selling the energy output through long-term power purchase agreements with utilities, and commercial and industrial customers. The contracted nature of these sales means revenues from this segment are also quite predictable.

NEER owns and operates about 36 GW of generation capacity today, and the firm expects that figure to roughly double in the next two years. Combined with FPL’s rate base growth and offset by anticipated equity issuance, this expansion is expected to drive NextEra’s EPS to grow at an annual rate of 6% to 8% through 2027. If EPS increases at the midpoint of the expected range (7%) and NextEra’s P/E ratio (currently 18.3x, based on forecasted profits over the next 12 months) remains stable, then its stock price could rise by a similar amount. Throw in its current 3% dividend yield, and you could be looking at a roughly 10% annual total shareholder return over the next few years.

Constellation Energy – the nuclear play.

With power demand surging and policymakers cracking down on carbon emissions, nuclear energy is in a uniquely attractive position. Unlike renewables, nuclear plants provide a reliable and continuous source of electricity – 24/7, without interruption. And they produce zero carbon emissions during their operational lives, which span decades.

These factors explain why major tech firms have recently turned to nuclear energy to address one of their toughest challenges: staying aligned with their climate commitments while trying to meet the massive, nonstop power needs of their data centers. Microsoft, for example, recently announced a 20-year power purchase deal with Constellation Energy from a nuclear reactor that was in the process of being decommissioned. The reactor will be restarted in 2028 instead, and remain operational until at least 2054.

Notably, Microsoft will be paying a hefty premium for power compared to current market prices – a recognition that carbon-free electricity is more valuable when it’s available around the clock. The premium also implicitly reflects an expectation that power prices are set to rise in the future as demand surges.

That’s just part of what makes Constellation so interesting. The firm owns the biggest fleet of nuclear power plants in the US, operating 21 reactors and holding stakes in two additional ones. In fact, it has more nuclear capacity than all of its US competitors combined. It’s also a “merchant generator”, meaning its power plants sell electricity into the open market. That sets it apart from utilities, which earn a regulated return on assets. The merchant sector is, therefore, riskier, with its profits tied to volatile power prices (among other things).

Having said that, the deal between Constellation and Microsoft highlights how independent generators – especially those with nuclear plants – can secure long-term contracts with deep-pocketed tech firms to stabilize their sales and reduce earnings variability. What’s more, Constellation’s nuclear plants earn production tax credits for each unit of electricity generated, further boosting revenue visibility. Providing additional support are capacity payments – financial incentives paid to electricity generators to ensure they commit to providing reliable power during periods of high demand, helping maintain grid stability and prevent blackouts.

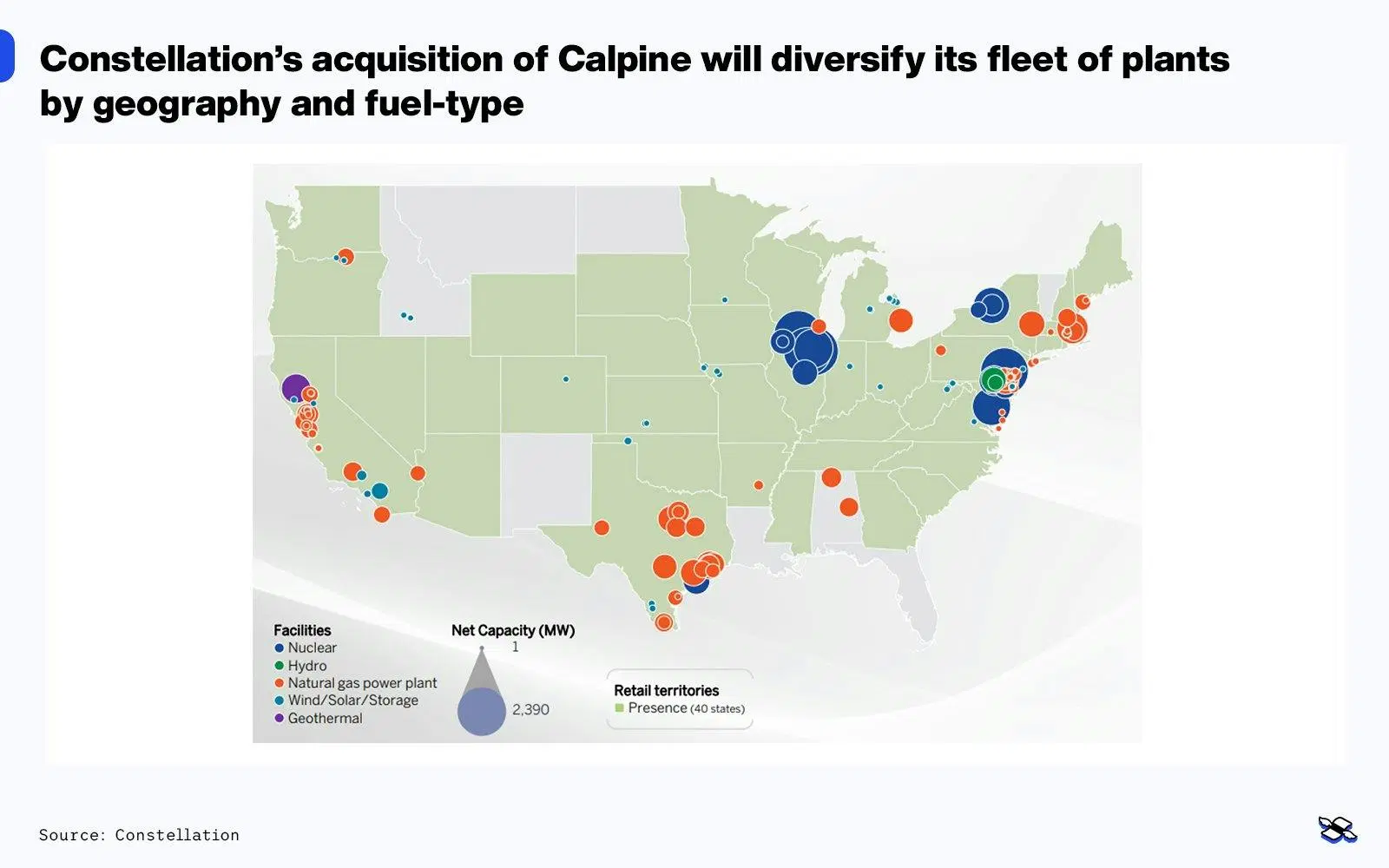

Constellation was in the news just last week, announcing it had struck a deal to buy rival merchant generator Calpine for $16.4 billion. The cash-and-stock deal is expected to boost Constellation’s EPS while diversifying its fleet of plants by geography and fuel type, since Calpine is heavily weighted toward natural gas and geothermal energy. Of course, the deal will mean that Constellation will no longer be a pure-play nuclear energy stock. On the flip side, that mix of nuclear and natural gas plants could give the firm greater flexibility in contract negotiations with major commercial and industrial customers.

Constellation’s acquisition of Calpine will diversify its fleet of plants by geography and fuel type. Source: Constellation.

Constellation is acquiring Calpine at a valuation of approximately 8x its projected 2026 EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization). That’s super attractive when you consider that rival Vistra trades at over 11x. What’s more, the deal is expected to boost Constellation’s EPS by $2 after accounting for the additional shares issued to fund the acquisition. For reference, the firm is estimated to have earned $8.40 in EPS last year and expects to grow that at a low double-digit rate through 2030.

Finally, despite a near-tripling of its stock price since the start of 2024, Constellation’s expected free cash flow yield (FCF) – a measure of how much money a company generates relative to its market capitalization – is 5.3% for this year. (Note that this is factoring in the yearly $2 billion of FCF that Calpine is expected to bring in.) Now that 5.3% doesn't imply the firm is a bargain, but it doesn't mean it's overpriced either. However, based purely on its forward P/E of 33x, Constellation is definitely trading on the expensive side for this sector. And that fact – coupled with its higher risk profile compared to regulated utilities – suggests you might want to allocate a bit less to this company, compared to the other two.

PART V: RISKS

Every sector has its risks, and with utilities, that includes rising bond yields, regulatory pushback on companies’ big investment plans, increasing financing requirements, and the possibility that those lofty power demand growth forecasts may have overshot the mark. Dominion faces big-project threats related to the huge offshore wind farm it’s building. NextEra is staring down regulatory uncertainty over FPL’s investment plan and potential changes to green energy tax credits. (A repeal or watering down of those tax credits would hurt Constellation’s nuclear business too.) Constellation also could run into snarls if power prices fall or if the integration of Calpine proves bumpy or expensive.

Let’s take a look at the potential risks for the sector.

First, if US bond yields continue to climb higher (as they have since September), that could weigh on the utilities sector’s valuation. That’s especially true considering that the sector’s forward P/E, relative to 10-year Treasury yields, looks slightly elevated at the moment.

Second, regulators could push back on utilities’ big investment plans. Upsized spending, after all, leads to higher customer bills – something regulators don’t like to see. This wasn’t an issue in 2023 and 2024, when utilities benefited from an environment of low natural gas and power prices. But if energy prices push higher again, utilities would have a tougher time managing bill pressure and getting big capital projects approved. Companies that focus on improving efficiency and cutting costs would be better positioned to navigate this risk, however, along with those transitioning their generation mix to renewable energy. That’s because wind and solar farms are cheap to run and have zero fuel costs – which brings down overall expenses.

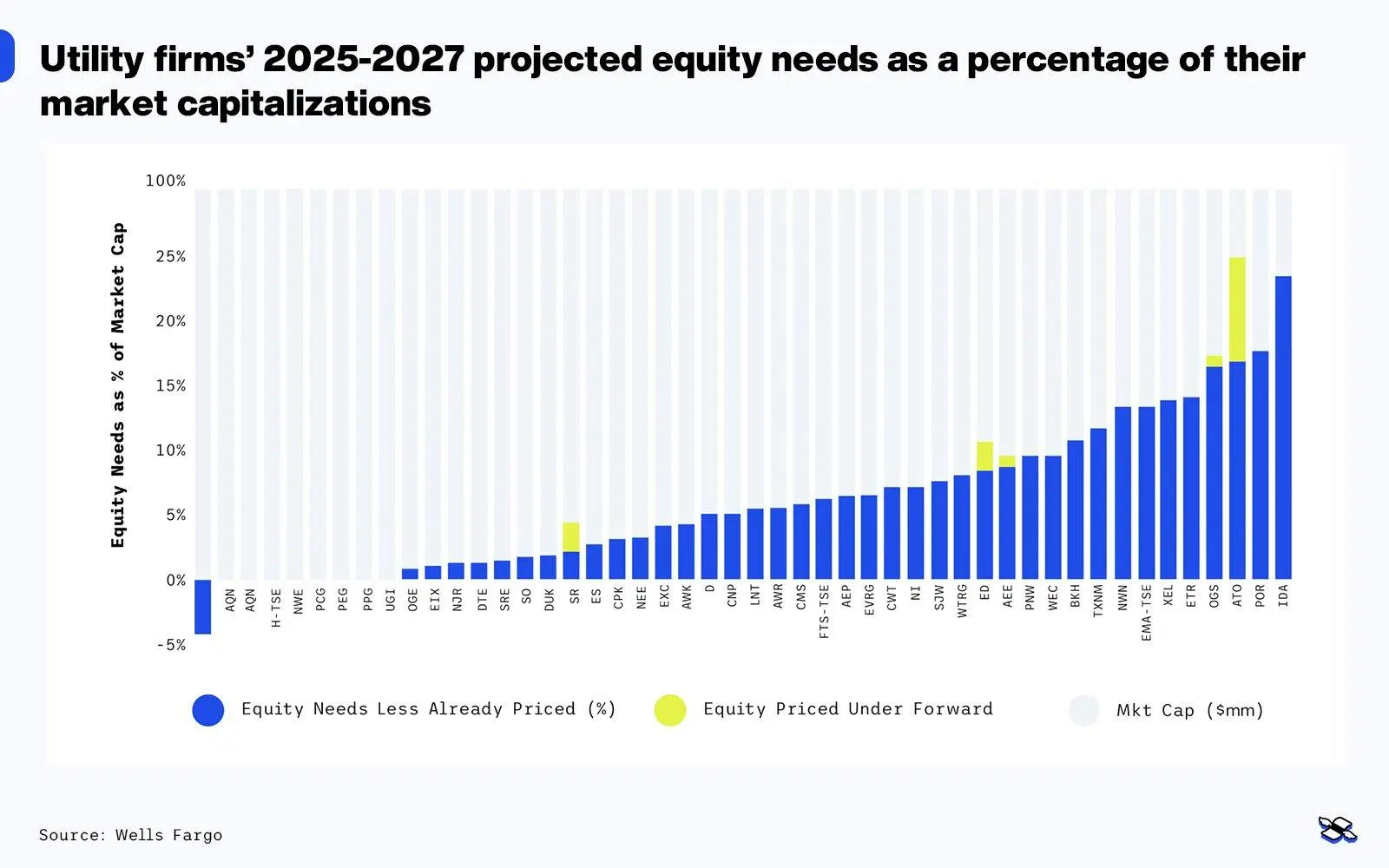

Third, utilities' big spending plans naturally mean more financing needs, with a lot of that funding expected to come from shareholders given the sector’s already elevated debt levels. That’s why most utilities have external equity needs. Recall that issuing new equity dilutes EPS, and this dilution becomes more pronounced if a utility's stock price declines – since that forces the company to sell more shares to raise the same amount of capital.

Utility firms’ 2025-2027 projected equity needs as a percentage of their market capitalizations. Source: Wells Fargo.

Fourth, if the lofty power demand growth forecasts prove to be overly optimistic (perhaps because AI data centers suddenly become more energy-efficient), investors might hit the exits, sending shares lower.

There are also some stock-specific risks to watch out for.

Dominion is currently building the US’s biggest offshore wind farm – a mammoth 2.6 GW facility with a price tag of almost $10 billion. That increases the riskiness of its rate base growth. After all, a utility expanding its rate base through lots of small and necessary projects – such as electrical grid upgrades – is less risky than a utility relying on one or two huge power plants. Not only is rate base growth uneven in the latter case, but such mega-projects are prone to delays and cost overruns. Dominion’s original budget for this one, for example, was $8 billion.

Adding more to the project’s uncertainty, president-elect Donald Trump has vowed to kill offshore wind energy development “on day one” of his second term (i.e. Monday). That’s a serious threat, especially considering that offshore wind lease sales are run by the Department of the Interior, which will be directly under Trump’s purview.

As for NextEra, expect some noise and uncertainty as regulators review and propose changes to FPL’s multiyear investment plan, which is set to be filed in 2025. It could take up to a year for the review process to conclude, and only then will investors get a clear picture of FPL’s rate base growth for the second half of the decade. For NEER, the big risk is the possibility of the new US administration repealing some or all of the generous tax credits provided to green energy under the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. That would slow the development of wind and solar farms in the US, denting NEER’s earnings growth.

Any repeal of these tax credits, which also apply to nuclear energy, would similarly harm Constellation. However, this risk is arguably lower, given that Trump and his Republican Party have generally been supportive of nuclear power. The bigger threats facing Constellation are the potential for falling power prices and the possibility of a bumpy, costly integration of Calpine.

---

Capital at risk. Our analyst insights are for educational and entertainment purposes only. They’re produced by Finimize and represent their own opinions and views only. Wealthyhood does not render investment, financial, legal, tax, or accounting advice and has no control over the analyst insights content.