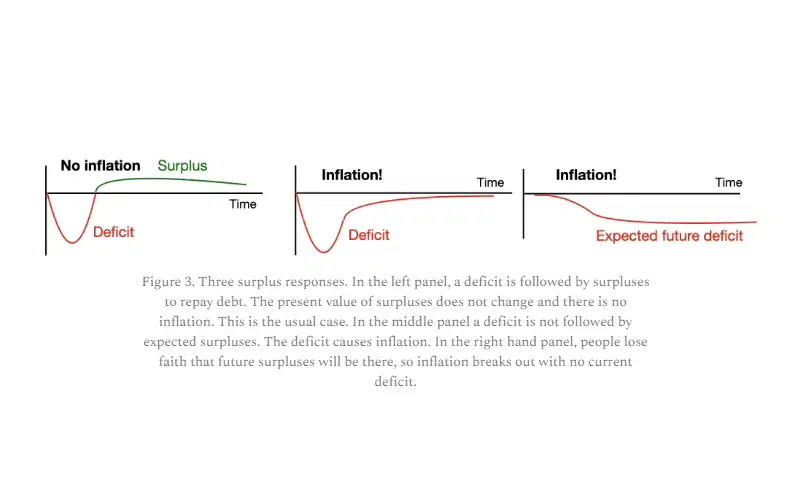

The fiscal theory of inflation says that prices adjust to make the real value of government debt equal to the expected future surpluses. When there’s a big deficit that people don’t think will be paid off, that leads to inflation. The theory’s got a strong track record and accurately predicted the pandemic-era inflation spike.

If the theory’s true, it can have big implications. It means central banks will never be able to control inflation on their own, high interest rates might actually increase inflation by boosting the deficit, responsible fiscal policies might be the only thing that can stabilize things, and investors’ confidence in the government’s ability to repay its debts is ultimately what matters most.

The theory suggests that with pandemic-related stimulus over, inflation should stabilize, but new borrowing without budget reforms or a rise in skepticism about government debt repayment could reignite it.

Central banks and interest rates can influence inflation in the short term. But, according to a little-known theory, government debt – and whether the public expects it to be repaid – determines its path over the long haul. And with governments spending more than they earn – and the cost of paying interest on the debt it builds going up and up – you may want to keep a close eye on that. Here’s how the theory works and what it says about what might happen next.

What’s the theory, then?

It’s called the fiscal theory of inflation (or the fiscal theory of the price level), and it essentially throws the conventional wisdom about price pressures out the window. So, forget what you’ve heard about inflation being a consequence of too much money chasing too few goods (or services). This theory says that inflation happens when government debt piles up high enough that it makes people question whether it’ll ever be paid back.

Imagine the government as a big company that can issue shares and bonds (in other words, money and debt). Investors value these based on the company’s future profits (future tax revenues). When investors think the company has issued more shares and bonds than it can pay back with its future profits, they’ll start to worry. They’ll begin to fear that the company will have to devalue those shares and bonds – and, in the case of the government, that means they’ll expect inflation to shrink the real value of that money and debt.

And that tends to change people’s behavior. To avoid holding onto potentially worthless shares and bonds, people will start spending their money quickly to buy the things they want before their currency loses value. This rush to spend drives up the prices of goods and services – that’s inflation. For prices to stabilize, the government will need to convince people it can cover its debt. They can do this by raising taxes or cutting spending to generate enough surpluses (money left over after expenses) to pay off the debt over time. Of course, they could also let inflation reduce the burden of that debt – because the amount of money owed doesn’t change, even as prices go up, so, in effect, you’re paying what’s owed with less valuable dollars.

In short, inflation under this theory happens when people think the government has borrowed more than it can pay back without resorting to inflationary measures. John Cochrane – the latest high-profile economist to work on the theory – explained it all perfectly. “Prices will adjust until the real value of all government debt, including money, equals the present value of current and future government surpluses.”

Here’s what that could mean. The US government owes about $25 trillion, with all the bonds it’s issued. So people need to believe that taxes will exceed spending over time by $25 trillion to cover that debt. If (and this is a hypothetical example) they think only $12.5 trillion will be repaid, they’ll ditch some of their government debt to buy other things, pushing prices up. This will continue until all prices have doubled, making that $25 trillion promise worth just $12.5 trillion in today’s money.

Why should you care?

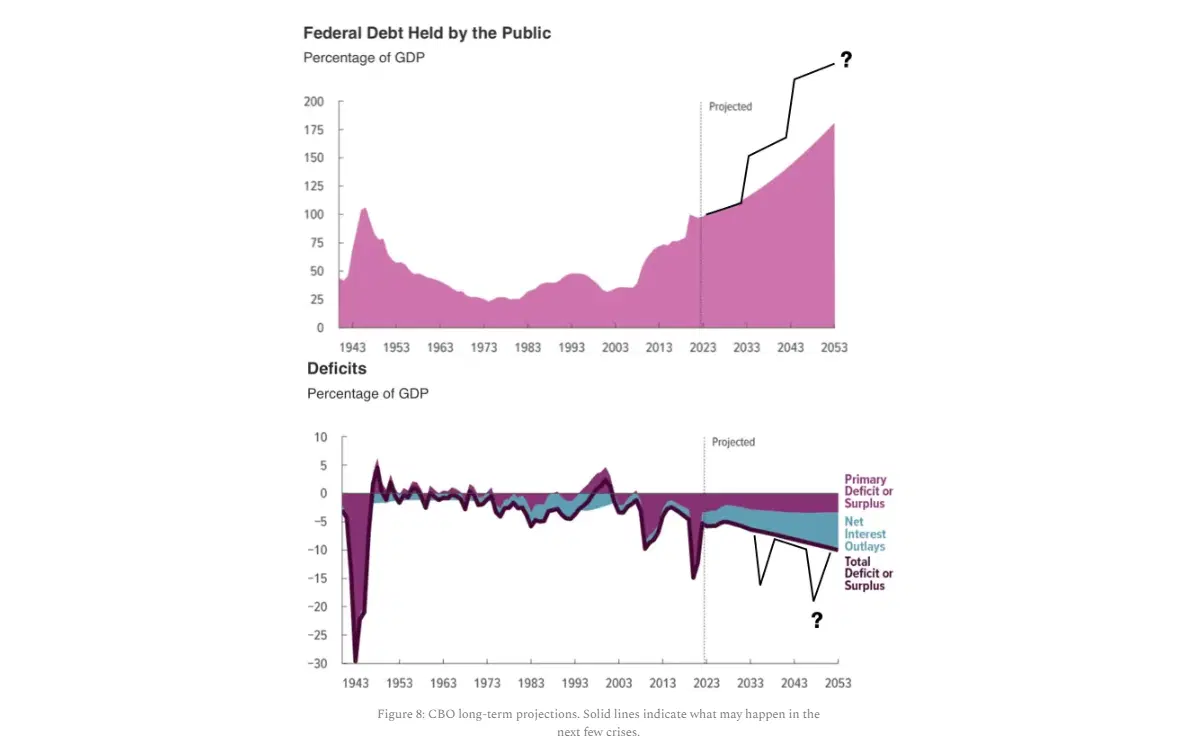

Well, the mix of record government debt, widening deficits, and growing doubts about how the US will pay for it all could keep inflation higher for longer. And it could also have broader implications.

Central banks alone can’t crush inflation. As you probably know, central banks have been jacking up interest rates in their battle against hot inflation, hoping that will suppress borrowing and spending enough to dampen prices. But those moves don’t address the underlying issue of unsustainably high government debt. So what this theory tells you is that without changes in government spending, the central bank’s arsenal might not be enough to defeat inflation.

High interest rates could make inflation worse. Brace yourself for this one. High interest rates might actually worsen inflation. Here’s why: raising rates can increase the government’s debt burden. Higher interest payments mean bigger budget deficits, which may freak out investors even more. This loss of confidence could lead to more spending today and higher prices – a vicious cycle.

It’s all about confidence and psychology. The theory is less about the total amount of debt and more about whether people have faith in the government’s ability to repay it. If folks believe the government can manage its debt (even a lot of debt), they stay calm. It’s only once they lose confidence that they start spending their money quickly, leading to inflation. It’s all about psychology – and history shows us just how temperamental that can be.

Only sound government spending policies can turn this ship around. To keep confidence high, governments need credible and transparent fiscal policies, ideally coordinated with their central bank’s monetary policy. That’s tough to pull off – and even tougher ahead of an election or during political upheavals.

How solid is this theory?

The theory explains historical episodes of inflation – and lack of inflation – perhaps even better than the competing, more commonly accepted theories.

For example, Germany’s post-World War I hyperinflation occurred after the government printed money to pay debts without a credible plan for future surpluses, triggering a loss of confidence and skyrocketing prices. It was brought back under control in 1923 when Germany introduced a new currency and credible budget reforms, restoring stability.

Or, another example: during America’s great inflation of the 1970s, the country was facing huge deficits and coping with the collapse of the Bretton Woods “gold standard” system, both of which caused a loss of confidence in fiscal discipline and rising prices. In the 1980s, the US managed to wrangle inflation – partly with high interest rates, but also by making huge spending adjustments, which restored people’s faith in its fiscal sensibilities.

But there are three episodes where the theory really proves its worth, addressing many features of history that conventional theories don’t account for well.

The first is the lack of Inflation after the global financial crisis of 2008-09. If you were going on conventional theories alone, you’d have expected inflation to perk up after the crisis because of ultralow interest rates and the impact of central banks’ massive bond-buying programs (which are known as quantitative easing, or “QE”, and are seen in the market to have the effect of “printing money”). All that stuff was supposed to boost spending and prices. But they didn’t really: inflation stayed low and stable. And the fiscal theory of inflation can explain why. For starters, that QE was really just a swap of short-term debt (i.e. money in the banks’ reserves) for longer-term debt (government bonds), so that didn’t impact fiscal policy. And sure, deficits were high, but people believed the governments would repay their debt through future surpluses, keeping inflation expectations and actual inflation low. Of course, low interest rates made the debt payments easier to stomach, and the idea of “secular stagnation” – a prolonged period of low growth, low interest rates, and low inflation – also helped tame inflation expectations. But according to proponents of the fiscal theory of inflation, if price rises remained well-behaved, that was mostly thanks to the trust in future fiscal discipline.

The second is the Covid-linked inflation surge. During the pandemic, governments took unprecedented measures, spending over $5 trillion – a 30% increase on the $17 trillion debt outstanding in fiscal stimulus before Covid. And this time, there was less focus on how that debt would be repaid. Without a clear plan for future fiscal surpluses, confidence in the government’s ability to repay its debt without causing inflation dwindled. And as the fiscal theory of inflation suggests, an enormous deficit that people don’t expect to be fully repaid stokes inflation. Somewhat surprisingly, the fall of inflation since the peak is also consistent with the theory: a one-time fiscal boost causes a one-time price level rise, erasing some of the real value of the debt. Prices stay elevated, but inflation eventually fades – on its own – once that adjustment is complete.

The third episode is Japan’s decades-long lack of inflation. The country has had high debt and low interest rates, so you would have expected at least some inflation. The fiscal theory of inflation explains why it didn’t for so long and, yep, it comes down to public confidence in the government’s fiscal policy. In Japan, even though the debt load is more than double the size of the economy, real interest rates have been super low for decades. That’s kept the payments on the debt manageable and has allowed the Japanese government to maintain its reputation for solid fiscal discipline. As a result, people trust that the government will be able to manage its debt without resorting to inflation, keeping price stability and price stability expectations intact. And this tells you something important: that as long as there’s confidence in the government’s ability to manage its finances, high debt levels don’t necessarily lead to high inflation (although it certainly increases the risk of it).

Now, like all economic models, the fiscal theory of inflation has its flaws. It’s great at making sense of past events, but predicting the future is a whole different ball game (and theories generally work until they don’t or until they’re replaced by a new one that explains things better.). Sure, it correctly predicted the outcome of past inflation episodes, but it’s hard to tell how much of that was coincidence. See, it’s tough to test the theory empirically because you can’t really separate the impact of fiscal policy from other factors, and future government budget plans are always tricky to predict. What’s more, the theory doesn’t nail down when and why people lose confidence in the government’s ability to repay its debt.

And what does the theory say will happen next?

Here’s the good news: if those “one-time” pandemic stimulus programs are over, then the fiscal theory of inflation suggests that high inflation is likely over too. Prices will remain at a permanent high (they’ve inflated away a good portion of the new debt), but as long as there are no new deficits – or as long as new deficits are balanced by future surpluses – we should return to price stability.

However, two threats linger. First, without budget reforms and better bondholder assurances, new borrowing could rekindle inflation. Second, growing doubts about the government’s ability to repay its massive debts could lead people to sell their bonds and spend money quickly to avoid holding devalued currency – and that could spark new price pressures.

Just because inflation might dip in the short term doesn’t mean the danger’s gone. As long as governments are buried in debt and running big deficits without clear plans to balance the books, the threat of inflation remains high. So stay vigilant: keep an eye on government plans for managing their debt and deficits, and watch how investors and the public respond, paying particularly close attention to inflation expectations and the “term premium” – the additional interest that investors demand to hold longer-term bonds over shorter-term ones.

And just to be safe, you might consider investing in assets that have the potential to hold at least some of their real value. While there’s no sure thing, my top two picks for hedging fiscally driven inflation would be gold and bitcoin, followed by real estate, commodities, and stocks with strong pricing power. It’s perhaps no coincidence that my top two have been skyrocketing lately…

-

Capital at risk. Our analyst insights are for educational and entertainment purposes only. They’re produced by Finimize and represent their own opinions and views only. Wealthyhood does not render investment, financial, legal, tax, or accounting advice and has no control over the analyst insights content.