China’s population is shrinking and that’s expected to have major repercussions for its labor market, demand for products and housing, public finances, and more. Ultimately, the situation will cut into the long-term growth potential of the country’s economy.

Policymakers are likely to try to offset the decline in its workforce with productivity gains. And you can convert that into an opportunity by investing in automation firms with large exposures to the country, or via the Global X China Robotics And AI ETF.

In response to China’s aging population, the government has announced a big economic plan to cater to older people. That push would provide a boost for the country’s healthcare firms, which you can tap into via the Global X MSCI China Health Care ETF.

China just isn’t getting any younger. Its population continued a historic decline in 2023, falling for the second year in a row to 1.409 billion. And this aging process involves a lot more than crow’s feet: it will impact the country’s economy and beyond. But it’s also expected to create a new wave of investment opportunities as the government adjusts its spending to the evolving demographic and consumption trends. Here’s how to invest gracefully with this age trend.

Why is China’s population shrinking?

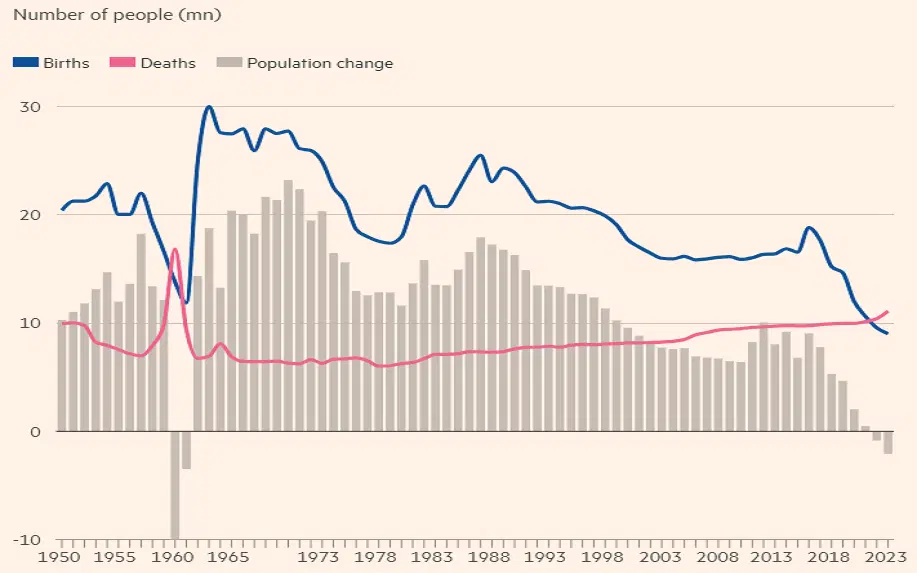

The short answer: fewer births and more deaths. But mostly, fewer births. Despite recent efforts by the government to encourage families to have more children, there were just 9.02 million babies born in China last year – the lowest recorded since the country’s founding in 1949. Meanwhile, there were 11.1 million deaths in the country, the most since 1960, after authorities hastily lifted strict pandemic curbs. That meant China’s population dropped by 2.08 million – about twice the decline seen in 2022 when the Chinese population shrank for the first time since 1961, the final year of the Great Famine.

China’s population shrank last year as births fell to a record low and deaths rose. Source: FT.

Chinese authorities said the drop in births is the beginning of a new trend, blaming it on a fall in the number of women of childbearing age, and on couples who are opting to delay marriage and pregnancy or deciding not to have children at all. More critical observers also suggest that there’s a mutually reinforcing cycle between the country’s stuttering economy and the low birth rate. They expect the lifelong financial commitment of having a child, coupled with prevailing economic pessimism, to thwart the government’s hopes of boosting the birth rate – especially since big swathes of the population have moved from China’s rural farms into cities, where having children is more expensive.

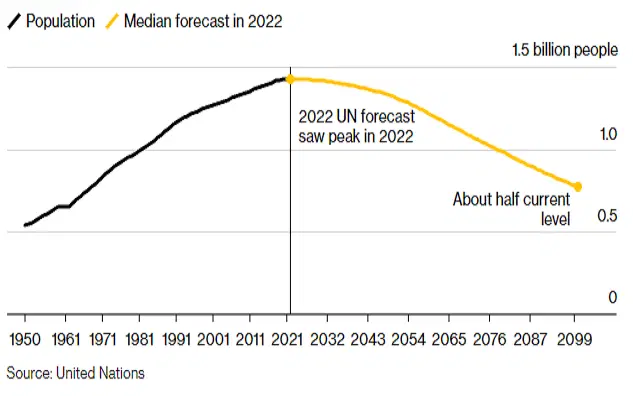

If the population plunge is tough to deal with, it’s made worse by the fact that it came much faster than previously expected. Back in 2019, the United Nations was forecasting that China’s population would peak in 2031 – and then decline. But a couple of years later, it revised that forecast, estimating a peak at the start of 2022. Longer term, UN experts see China’s population shrinking by 109 million by 2050.

China’s population peaked in 2021 and is forecast to steadily decline from now. Source: Bloomberg.

China now is following in the footsteps of other major economies in East Asia, like Japan and South Korea, which have seen their birth rates plummet, and their populations age and shrink as they’ve become wealthier and more developed. Japan is particularly noteworthy: the country entered three decades of economic stagnation in the early 1990s that coincided with its aging demographics. During that period, Japan also grappled with persistent deflation, a challenge that China is beginning to face today. A price measure of all the goods and services produced within the Chinese economy, for example, contracted for three quarters in a row in 2023, marking the longest slide since 1999.

How will a shrinking population impact China’s economy?

China’s shrinking – and rapidly aging – population is expected to bring further troubles to the country’s flagging economy, in part by reducing the size of the workforce that drives growth and funds pension systems. But the long-term repercussions here are wide-ranging and extend well beyond China’s labor market. They’ll affect consumer and housing demand, the country’s public finances, and more, and will ultimately cut into the long-term growth potential of the economy while fueling further doubts on whether it will ever overtake the US in size.

In the labor market

Last year, 61% of China’s population was of working age, which the government defines as 16 to 59. That’s down from about 70% a decade ago and is expected to continue to fall.

Bloomberg Economics predicts the group will slump to about 650 million people in 2050, from 865 million in 2023. This matters because, broadly speaking, there are two main sources of economic expansion: growth in the size of the workforce, and growth in the productivity (output per hour worked) of that workforce. So put simply, a decline in China’s workforce will directly dent economic growth unless the drop can be offset by productivity gains (more on that later).

Plus, as the pool of available workers shrinks, hourly wages will increase. And that’s a tricky situation for a country whose cheap labor has helped it become known as “the world’s factory”. If factories relocate to countries with cheaper labor (think: Bangladesh, India, Vietnam, and so on), then China’s manufacturing activity – and, by extension, its economy – will take a hit.

In housing and products

Fewer people will mean less demand for goods and services, and that’s likely to complicate China’s transition from an investment-led to a consumption-led economy. What’s more, with fewer people starting families, there will eventually be a hit to long-term demand for houses. That could further drag down China’s real estate sector – a crucial growth engine that accounts for 20% to 30% of the economy.

In public finances

China’s population is getting older: official projections suggest 30% of its residents will be 60 or over by 2035, up from about 21% today. That puts the country’s public finances in a tough spot, reducing the government’s income (from taxes) while increasing its expenses (through healthcare and pension programs). Look at it this way: five workers supported every Chinese retiree in 2020, but estimates show the ratio declining to 2.4 workers in 2035 – and 1.6 in 2050. That strain on China’s public finances will dent its ability to splash out on growth-generating projects like infrastructure, education, and defense. And that will slow an important engine of growth: government spending is a big part of the Chinese economy, accounting for more than 15% of its economic output every year since 2011.

What’s the opportunity here?

Suppose China wants to keep growing at a healthy rate and achieve a politically motivated goal of having its economy overtake the US’s in size. In that case, it would have to offset the decline in its workforce with productivity gains – that is, an increase in the economic output per hour worked. China could do that in several ways: for example, by increasing access to the latest equipment, relying more on automation technology like robotics and AI, investing in education and training, improving infrastructure, encouraging business growth and innovation, or boosting research and development.

Of the lot, technology is arguably the most important in improving productivity. Think about how much we can do today using computers, compared to a few decades ago, and how much that’s boosted economic output per hour worked. So in an economy where the workforce is falling, you could offset those declines with automation technology like robotics and AI.

If you want to convert China’s shrinking population into a long-term investment opportunity, you probably want to screen for firms in the automation sector with major exposure to the country. An easy way to tap into a diversified portfolio of these firms is via the Hong Kong-listed Global X China Robotics And AI ETF (ticker: 2807; expense ratio: 0.68%).

Finally, there’s another interesting opportunity arising from China’s changing demographics. In response to its aging population, the government just announced a plan for a “silver economy” to cater to the elderly. Authorities estimate that the silver economy, consisting of all the goods and services targeted to older people, will be worth an estimated 30 trillion yuan ($4.2 trillion) in the next decade, accounting for 10% of China’s overall economy by 2035. These goods and services range from meal delivery to nursing homes and entertainment options. But health-related consumption, ranging from medical devices to pharmaceuticals, would account for by far the biggest share of spending by this age group.

That push would provide a welcome boost for the biggest local biotech and pharma groups, including Jiangsu Hengrui, WuXi Biologics, Shanghai Fosun Pharma, and Sinopharm. These firms were hurt last year by an industry slowdown as the sector’s Covid boost wore off, with many of them seeing their share prices fall. But that could provide long-term investors with an attractive entry point. Having said that, investing in individual biotech and pharma companies could be quite risky, so perhaps a better approach is to invest in a diversified portfolio of these firms via an ETF, such as the Global X MSCI China Health Care ETF (ticker: CHIH; expense ratio: 0.65%).

-

Capital at risk. Our analyst insights are for information purposes only.