The rule of 40 is used widely in the technology industry as a benchmark for firms looking to balance sales growth and profitability. Those that make the cut get rewarded with high valuations.

When trying to pick from the elite group, remember: firms that are able to balance a slowdown in sales growth with offsetting profitability improvements will generate the most cash, which is ultimately the most important thing for long-term investors.

The Magnificent Seven tech stocks almost all pass the test. But Amazon falls short and Apple stands right on the edge.

For the Magnificent Seven tech companies, the AI revolution has been like rocket fuel – launching their stocks and their popularity to some astronomical heights. So it can’t be a huge surprise that folks are whispering about bubbles and asking whether those shares have gone too far. And that makes this a good time to assess the risks, using the rule of 40 – popular blogger Brad Feld’s simple performance measure.

What’s the rule of 40?

It’s a simple enough idea: combined sales growth and profit margins should exceed 40% – no matter the firm's age. Ideally, this should be over a multi-year period, not a one-hit-wonder-year. The rule implies that young tech firms motoring at 40% or more sales growth needn’t worry about profit margins: they can wait. But when the gray hairs of age start to show and sales growth slows, investors will want to see profit margins moving higher to compensate. And firms looking to live out their golden years on 10% or slower growth will need at least 30% in profit margins to retire fat and happy.

Whether Feld plucked 40% out of thin air only he knows, and it’s by no means a binary thing where only firms hitting the hurdle do well and all others fail. But the rule’s been widely adopted by tech company bosses as an internal benchmark to hit, and there’s plenty of evidence to suggest it’s important for investors too.

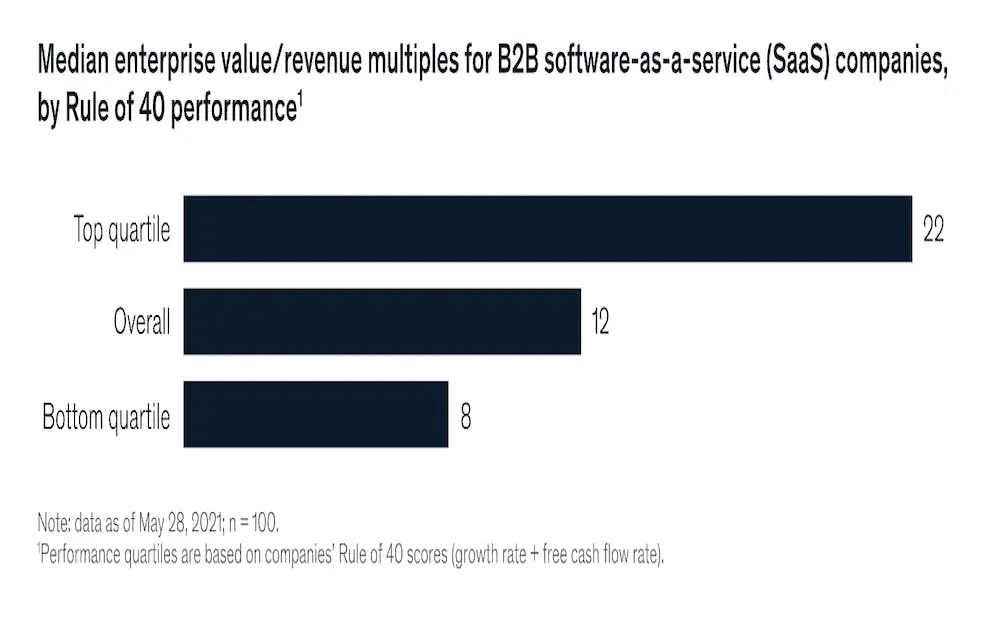

Take a look at the following chart, which is from a McKinsey study in 2021. The consultancy analyzed 100 publicly traded US SaaS companies with revenues of $100 million or more, all scoring at or above the rule of 40. The researchers used free cash flow margin (cash after all day-to-day expenses and big project outlays as a percentage of sales) for their profit measure. The results showed that the top 25 scoring firms traded at an average total enterprise value to revenues (EV/revenue) valuation of 22x. That’s almost twice the overall average and nearly three times the average valuation of the lowest-scoring 25 firms.

Source: McKinsey & Company.

In short, the better a firm scored on Feld’s sales growth + profit margin measure, the higher the valuation investors were prepared to pay. What’s more, even the lowest-ranking members of the club commanded a lofty 8x revenue valuation.

How can you use the rule of 40?

Grab a firm’s five-year sales growth and profit margin from annual reports or free investment tools like Koyfin. On margins, the most widely used measure is earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) as a percentage of sales.

Here’s the thing you want to remember when you’re peering through your rule-of-40 lens: when you boil it down, only one thing matters in stock investing – cash. Without producing cash, companies can’t invest in themselves to grow, they can’t repay shareholders with dividends or buybacks, and ultimately, they won’t survive.

And for companies to produce lots of cash over time, they must be able to grow and be profitable. One without the other doesn’t work. Sure, a firm can grow sales at 100% or more a year – and in the early days, investors will be attracted to that – but if it never produces a dollar of profit, ultimately, it's a worthless investment. On the flip side, profitability is great, but without growth, cash flow production often stagnates. There’s only so much cost firms can cut to boost cash flow, after all.

That leaves the middle-ground companies – those able to balance growth and profitability. These firms stand the best chance of producing the most cash over the years. It’s time for an example…

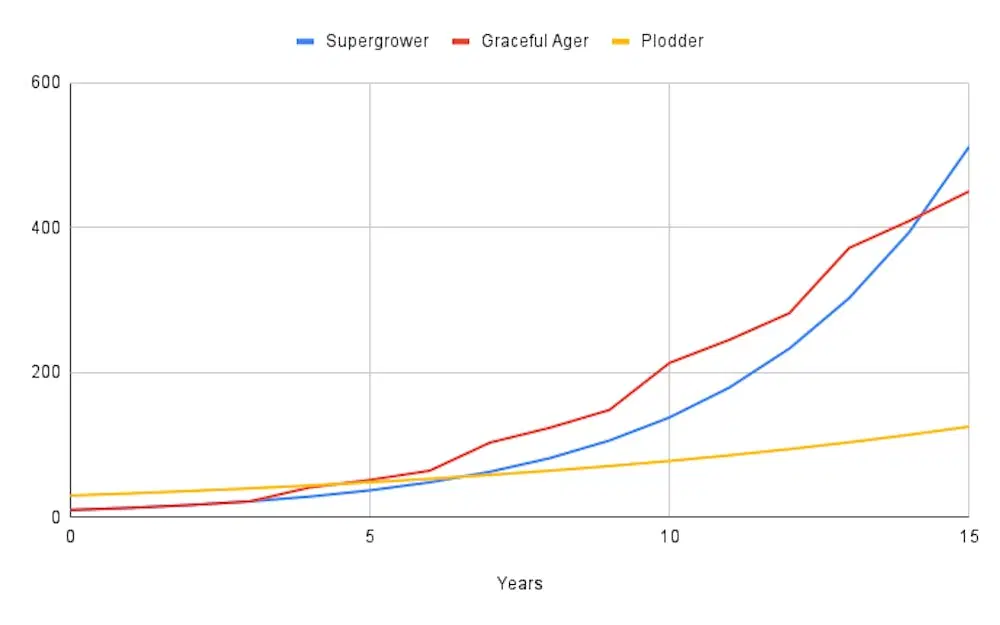

The chart below shows the annual profit from three made-up companies all conforming to the rule of 40. All our fictional firms start with $100 in sales. The supergrower (blue line) pulls in sales growth of 30% a year for 15 years with static 10% profit margins. Our graceful ager (red line) experiences step downs in sales growth every five years from 30% to 10%, but with offsetting margin increases from 10% to 30%. And our profitable plodder (yellow line) ticks along with 10% sales growth – not exactly pedestrian, we know: it’s still a member of the 40 club, after all – and 30% margins.

Over the 15-year period, our supergrower churns out just under $2,200 of total profits and our plodder $1,100. Leading the pack, though, is the graceful ager. By trading gradual sales growth declines for margin increases, the firm manages to cross the line with total profits of $2,600.

Notice two other things in that chart. Firstly, the plodder falls way behind in terms of profit production. And secondly, our supergrower does catch up to the graceful ager eventually. But here’s the thing: very few – if any – firms can sustain 30% sales growth for 15 years. Usually, competition floods the market and takes a slice of the pie.

Which of the Magnificent Seven make the cut?

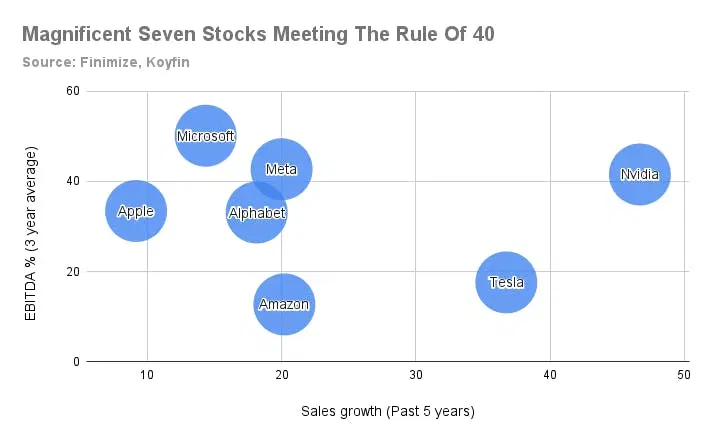

Below are the most popular stocks in the world right now – the Magnificent Seven – riding high on the crest of the AI wave. The chart below shows the distribution of their three-year average EBITDA margin and average sales growth over the past five years.

Sources: Finimize, Koyfin.

They are – perhaps unsurprisingly – fast-growing, profitable companies, by and large. But two things stand out. First, Amazon: when you add its sales growth of 20% to its EBITDA margin of 13%, you get 33% – way short of the all-important 40. And second, Apple: its 9% sales growth and 33% EBITDA margin bring it to 43%. That’s over 40, sure, but not by much. Considering the others are so much further ahead (Alphabet at 51, Meta 63, Microsoft 64, Nvidia 88, and Tesla 54), you’d perhaps be wise to rebalance your Magnificent Seven tech holdings toward the leaders and away from the two laggards.

And yeah, picking stocks does require a more complete picture than what’s offered here, with just sales growth and profit margins. But if you’re thinking about investing in tech firms, this chart – and the rule of 40 – could serve as a good starting point for your research. Just make sure you’re looking for firms that can balance growth and profitability: they stand the best chance of producing the most cash over time. Happy hunting…

-

Capital at risk. Our analyst insights are for educational and entertainment purposes only. They’re produced by Finimize and represent their own opinions and views only. Wealthyhood does not render investment, financial, legal, tax, or accounting advice and has no control over the analyst insights content.