The 1970s saw two major inflation spikes in the US, driven by expansive government and central bank policies, the collapse of the international Bretton Woods system, and a couple of severe oil crises. It all culminated in a period of stagflation that challenged existing economic theories and led to significant policy shifts in the early 1980s.

Sure, there’s a whiff of the 1970s in the air – with our global economic shifts, fat fiscal deficits, long stretches of easy-money policies, geopolitical tensions, commodity price pressures, and wage increases. But don’t forget, we’ve also got a few new tricks up our sleeve: a Fed that’s quick on the rate-hike draw, an economy that’s less reliant on foreign oil, structural factors that keep inflation in check, a more adaptable labor market, and fairly stable inflation expectations.

Current signs point away from a major inflation spike unless there’s a big energy or supply curveball. But let’s be real: predicting inflation is more art than science, and you can’t always account for everything. So, even when the outlook is chill, you might still keep an eye out for market shake-ups and the unexpected twists that come up along the way.

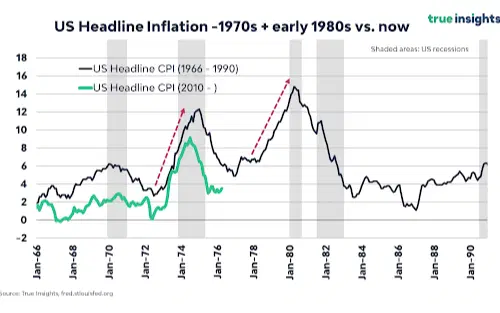

Inflation’s recent behavior has been a bit of a throwback to the 1970s: there was a sharp spike in consumer prices, followed by a swift, but partial, pullback. And lately, there have been signs that inflation might be heating back up again. So that’s got people worried that we might be on the brink of another major surge – just like we saw all those decades ago. I had a look back at that not-so-groovy time, and here’s what I found…

What went down in the 1970s?

Oh, the ’70s: era of disco, bell bottom jeans, and economic wild rides. It kicked off chill, with mild inflation, but things got heavy pretty quickly, with not just one, but two massive inflation spikes. The first happened in late 1974 and reached 12%, and the second came six years later, peaking just above 14% (black line).

The US saw a double wave of inflation in the 1970s. Source: True Insights, St. Louis Federal Reserve.

And you can see why that’s got some people on edge. Compare the modern day against the 1970s, and it looks like we are in the calm before a coming storm.

So, let’s try to understand what was driving inflation back in the go-go era.

For starters, it got going in the late 1960s as governments in big economies ramped up spending and cut taxes to keep unemployment low and growth robust, all without any real plan for balancing the books. Central banks played along, holding interest rates low and keeping the money supply flowing – and that’s kind of a perfect cocktail for budget deficits and inflation.

Then came a game changer: the international Bretton Woods monetary system collapsed in 1971. This system had replaced the previous gold standard, and had stabilized currencies after World War II by linking them to the US dollar, and linking the US dollar to gold. Its demise ushered in today’s era of freely floating currencies, led to a big drop in the greenback – which pushed inflation higher by raising import prices for Americans – and made some investors very nervous about what could happen in the future.

But things started to really get out of hand when two oil crises hit. In 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) cut off oil supplies to countries supporting Israel during the Yom Kippur War (including the US), causing oil prices to quadruple. And the Iranian Revolution disrupted oil supplies again in 1979, sending prices soaring even higher. And it wasn’t just oil prices surging: poor harvests pushed food prices up too, adding to the inflationary mix.

Governments tried to react (for instance by installing wage and price controls), but their moves often proved to be too little, too late, or were simply off-target, thanks to a shaky grasp of the factors that were actually driving the inflation. Plus, the classic wage-price spiral was in full effect: workers demanded higher wages to keep up with rising prices, which just pushed prices even higher (especially in industries with strong unions), and that led to more worker demands, and so on. Inflation expectations became entrenched among businesses and consumers, partly because of visible price hikes and wage demands, which exacerbated the inflationary spiral.

Now inflation might’ve been the biggest economic surprise of the day, but it wasn’t the only one: there was also stagnant demand and high unemployment (a.k.a. “stagflation”) – which upended the prevailing Keynesian wisdom that inflation and unemployment couldn’t rise together.

Eventually, the inflation was reined in, but at a not-ironically steep cost: in the early 1980s, Federal Reserve (Fed) Chairman Paul Volcker hiked interest rates in truly dramatic fashion, pushing them to 20%. The move successfully curtailed inflation but also triggered a deep recession and threw millions of people out of work.

This had profound and lasting effects: it spurred a shift toward “supply-side economics”, which called for tax cuts, deregulation, and reduced government interference – paving the way for the rise in shareholder capitalism and a sharp redistribution of economic benefits from labor to capital.

Could we be on the cusp of a 1970s-style inflation redux?

It does make you wonder. So let’s take a look at how today stacks up against the past.

There are a few striking similarities.

Government and central bank policies have been “far out”, as they say. Since the 2008-09 global financial crisis, government and central bank strategies have been super accommodative, with ultra-low interest rates and plenty of other spending and stimulus built into the system. And that all ramped up to a whole new level during the pandemic. Interest rates plunged to all-time lows – at times even dipping into negative territory – as hefty government spending juiced up consumer wallets and fueled growth. And much like in the ’70s, this spree has stretched the US government’s fiscal fitness, sparking fears about its ability to manage its debts.

Global shocks have been reshaping the scene. In the 1970s, the collapse of the Bretton Woods international system ramped up global uncertainty. And today’s landscape is similarly uncertain, shaken up by Covid-19, shifting trade patterns, energy-hungry technological advancements like AI and crypto, and huge structural shift toward green energy.

Oil and other commodity prices have been surging. Like the oil crises of the ’70s, recent geopolitical tensions – particularly the war in Ukraine – have triggered spikes in oil prices. The rising cost of other key commodities, such as copper and agricultural products, has also sent some old warning signals. That makes today’s environment quite prone to further commodity shocks.

Wages have been on the rise. Unionization isn’t as prevalent as it was in the 1970s, but there’s been a noticeable uptick in worker power due to labor shortages and increasing social unrest, enhancing employees’ ability to demand better wages to defend against future inflation shocks.

But, there are also some critical contrasts.

Oil dependency is not as strong. The US is now a leading global oil producer, and with more diversified energy sources worldwide, advanced economies everywhere are less vulnerable to oil supply shocks than they were back in the day.

Today’s inflation is “healthier”. Some of the inflation we’ve seen recently has been driven by gains in productivity – and that’s a positive sign. A robust rebound in manufacturing and consumer spending has also played a significant role, cushioning the adverse effects of inflation. What’s more, inflation expectations have remained “anchored”, meaning people expect them to hold within an expected range, and experts say that should help inflation move lower and prevent the disruptions from morphing into a prolonged price-wage feedback loop.

Central banks are more responsive now. After the 1970s, central banks became more independent and more responsive to what’s happening in the economy, with their credibility clearly tied to how well they manage inflation. And that’s why the Fed has already taken fairly determined steps to bring inflation down, raising interest rates at its most aggressive pace ever.

Economies are more deeply in debt. Relative to the size of their economies, government debt levels are much higher today than they were in the 1970s. (And the same is true of households and corportations.) For governments, the debtload could hamper their ability to adopt spending measures as a way of stimulating the economy. And unfortunately, this added financial strain makes today’s situation a bit unnerving.

The role of the government has been changing. Unlike the ’70s shift toward “neoliberalism” – an ideology characterized by deregulation and reduced political intervention – the role of the government in the economy has been growing, and there have been increasing calls for even more interventionist policies, some of which could fuel inflation. This, too, puts us in a less-than-comfortable position today.

So should you break out the lava lamp and wait for a second inflation spike?

For a second wave to really take off, you’d need the right economic environment and a catalyst. And the evidence is mixed on whether we’ve got the former. There are some echoes of the 1970s ringing through today’s economy (a changing global economy, worrying fiscal deficits, at least a decade of accommodative money policy, commodity price pressures, and the influence of rising wages). But there are also some significant differences (a more proactive Fed that’s already hiked rates aggressively, lower dependency on oil, structural downard pressures on inflation, a more flexible labour market, and inflation expectations that have so far remained anchored at reasonable levels).

For now, the differences would seem to outweigh the similarities, and a rational analysis tells us that unless there’s another big energy shock or supply shock that could act as a catalyst, another huge wave of inflation just isn’t likely.

Mind you, a rational analysis doesn’t always work when it comes to predicting inflation. Inflation is a tricky beast, and nobody – yep, not even the wizards at the Fed or the sharpest market experts – has completely cracked the code on how it works, especially when it starts to pick up speed. It’s a wild card, influenced by economic data and erratic human psychology. That’s probably why it’s caught markets off guard time and again, just like it’s done in the past couple of years. In fact, if you look at history, you’ll find that inflation has a habit of sticking around for much longer than expected and that “false dawns” are common.

There might not be another massive inflation spike in offing, but that doesn’t mean we’ll see a smooth glide back to the low and stable 2% inflation zone either. So you should probably brace yourself for higher and more unpredictable inflation – instead of the calm we’ve all become used to.

-

Capital at risk. Our analyst insights are for educational and entertainment purposes only. They’re produced by Finimize and represent their own opinions and views only. Wealthyhood does not render investment, financial, legal, tax, or accounting advice and has no control over the analyst insights content.