Hotter temperatures mean smaller harvests for many staple crops, which, in turn, leads to higher food prices and inflation. One study suggests the climate crisis will result in a rise in overall annual global inflation of up to 1.18 percentage points by 2035.

Central banks often ignore food prices from the inflation measures they target. That could change, but even if it does, their interest rate hikes wouldn’t be very effective against price rises caused by falling crop yields.

Climate change is expected to make agricultural commodity prices more volatile and cause them to increase over time. It’ll also open up opportunities to invest in agricultural technology companies that can enhance farm productivity and grow food in indoor settings.

What’s happening in agriculture?

Since the dawn of farming, one-off weather events like heatwaves, droughts, flooding, and untimely frosts have disrupted food production and pricing by ravaging harvests and driving up costs. But a more sustained trend is starting to lead to persistently higher prices: global warming. Put simply, hotter temperatures mean lower yields for many staple crops, resulting in less supply pulled from trees or the ground. Wheat yields, for example, fall dramatically when spring weather tops 27.8°C (82°F). And yet a recent study found that the major wheat-producing areas in China and the US are regularly experiencing temperatures above that threshold.

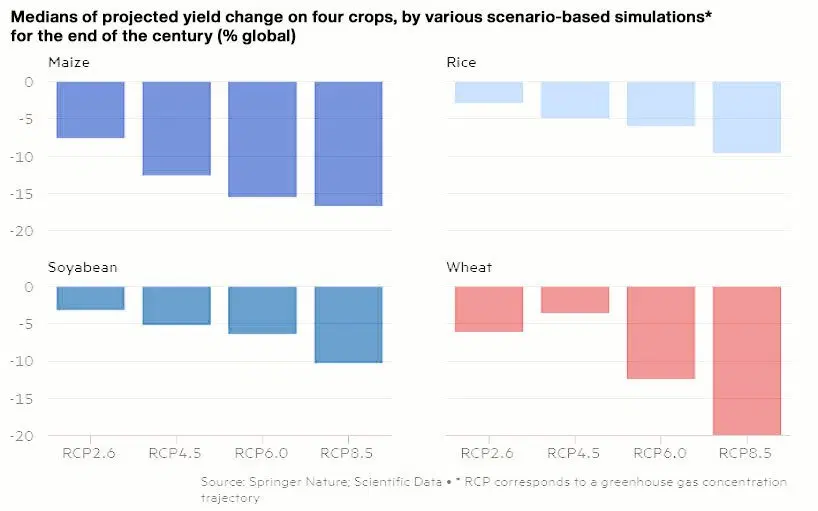

Severe climate change is likely to have a devastating impact on major crops. Source: Financial Times.

And when you’ve got lower crop yields and rising demand (to feed a growing population), you get higher prices. It’s also worth remembering that food demand is “inelastic” – meaning, people need to eat, regardless of prices.

Making matters worse, extreme weather events are becoming more common, and that’s chewing further into supply. For example, in Ghana and Ivory Coast, which account for two-thirds of the world’s cocoa production, heavy rainfall last summer fostered the humid conditions that were ideal for black pod disease to spread. This fungal infection caused cocoa pods to rot, severely affecting yields and sending prices to new records.

Besides reducing what can be harvested, climate change also affects food prices through higher “input” costs. Places that once produced abundant crops with just rainwater now require irrigation, thanks to drought conditions. And more and more pesticide use is needed to keep diseases and pests at bay. What’s more, today’s hotter weather reduces worker productivity in the labor-intensive farming sector, leading to steeper production costs.

Finally, as climate change increasingly shrinks crop yields, governments are more likely to adopt protectionist policies that could worsen the price impact. India, for example, enacted export restrictions on rice last year, which had consumers paying a lot more for that everyday staple.

What does this mean for inflation?

The answer here is tough to pin down. One study suggested that a third of the food price increases in the UK in 2023 was because of climate change. Another, by the European Central Bank (ECB), said food inflation in the bloc rose by around 0.67 percentage points in 2022 as a result of an exceptionally hot summer.

Looking ahead, higher temperatures are forecast to drive up global food inflation by as much as 3.2 percentage points per year over the next decade or so, according to research by the ECB and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. That would result in a rise in overall global inflation of up to 1.18 percentage points per year by 2035. Of course, different regions will be impacted differently. Crops in countries in Southern Europe, Africa, and South America are often the ones worst affected by rising temperatures.

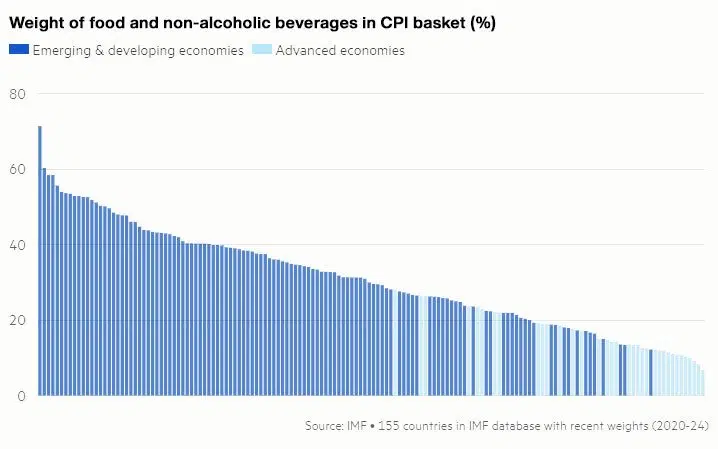

The impact on economies would vary too. In developing countries, food constitutes a bigger portion of household expenses – sometimes accounting for up to 50% of the consumer price index. That means any jump in food prices disproportionately affects overall inflation. What’s more, poorer countries are impacted more severely by bad crop harvests, because they find it harder to source their food elsewhere. That’s due to the fact that they’re less connected to global markets and lack the infrastructure needed to import food in big quantities.

People in developing countries spend proportionately more on food. Source: Financial Times.

Can’t central banks do something about higher food prices?

That’s very tricky. Inflation is definitely a chief concern for central banks, and when it gets too hot, they’ve got the most effective tool at their fingertips to cool them down – interest rate hikes. However, these policymakers typically respond to “core inflation” – the price measure that excludes food and energy because of their volatility.

Of course, that could change. As the climate crisis begins to lead to persistently higher food prices, there’s a growing argument that the focus should shift to overall inflation or, at the very least, a measure that excludes only energy prices. In other words, regarding spikes in food inflation as temporary won’t be practical anymore if the price shocks are happening more repeatedly and are persistently driving inflation higher.

It’s an important debate: the impact of rising food prices is felt heavily by ordinary citizens and feeds a lot into their inflation expectations. Put differently, people – even the folks in richer countries who spend proportionately less on food – often form their inflation expectations based on what their grocery bills are like. When those shoot up, they ask for bigger wages, which, in turn, tends to lead to higher overall inflation.

Now, let’s say central banks do start to pay more attention to food prices and act accordingly. That would lead to interest rates that are more volatile and higher over time (remember, these policymakers typically respond to a pick-up in inflation by making lending costs higher, which curbs borrowing and spending). But even that is subject to a lot of debate. After all, higher rates are more effective against demand-driven inflation than they are against price rises caused by supply shortages. To state the obvious, higher rates don’t lead to increased crop yields – the key thing driving food prices up.

In fact, some argue that higher borrowing costs could actually increase food inflation. See, farmers depend heavily on loans to buy equipment and other essentials, so higher rates would make it more costly for them to finance these necessities. As a result, they might pass on these increased costs to consumers, further driving up food prices.

The only way I think rate hikes could potentially help in this scenario (and I admit this is a bit of a stretch) is if a country imports the vast majority of its food. In that case, higher borrowing costs wouldn’t impact the input expenses of the farms it depends on, since they’d be predominantly located across borders. But they could lead to a stronger currency, since higher rates make it more attractive to international savers and investors. And that beefing up, in turn, would make it cheaper to import food from abroad.

Having said all that, there’s another complicating factor for central banks trying to respond to a food-related pick-up in inflation. See, when grocery bills shoot up, people have less money to spare on other things. That stifles broader consumer spending and stands in the way of economic growth, which, if anything, should push central banks to lower interest rates to avert a crisis.

So what is the right response?

That’s hard to say, but increasingly, experts are looking for solutions – like food price controls and targeted subsidies – led by government and industrial authorities, rather than central banks.

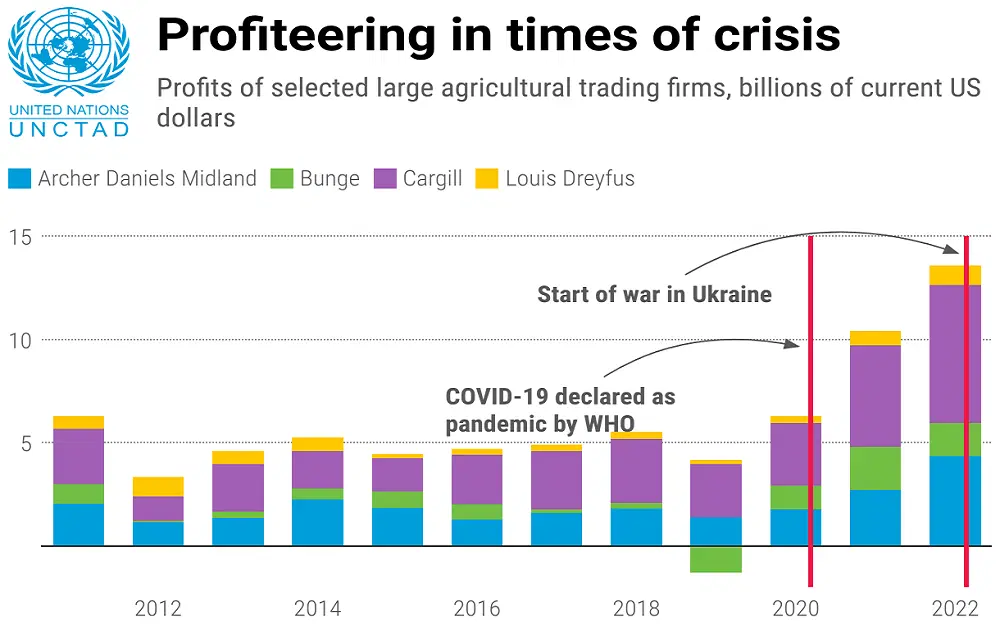

Stricter competition policies may also be necessary to prevent big corporations and commodity trading firms from profiteering during inflationary periods, which, of course, only aggravates the problem. For example, in a report last year, the United Nations criticized the world’s biggest four traders of agricultural commodities for making record profits in 2021 and 2022, while consumers faced a cost of living crisis.

The world’s four biggest traders of agricultural commodities saw their combined profits surge in 2021 and 2022. Source: United Nations.

Some folks are suggesting that countries should build up bumper stocks of food commodities to cushion against price fluctuations, and levy windfall-profit taxes against companies in essential sectors like food to deter price gouging.

What does this all mean for investors?

I’d say there are four big things to be aware of.

First, more volatile and persistently higher inflation will pose a new challenge for bond investors. These instruments are quite sensitive to both actual and expected inflation, and they often underperform when consumer price increases accelerate. That’s because the fixed amounts of future cash they offer investors become worth less as inflation rises.

Second, as climate change affects crop yields and food production, prices of agricultural commodities are also likely to become more volatile and increase over time. To hedge against that, you could consider investing in an ETF that tracks agricultural commodities, like the Invesco DB Agriculture Fund (ticker: DBA; expense ratio: 0.91%).

Third, there is growing potential to invest in agricultural technology companies that can offer solutions to improve crop resilience and increase farm productivity. Innovations in pest management, crop genetics, and precision agriculture could become increasingly valuable as farmers seek to mitigate the impact of climate change and increase yields despite challenging conditions. What’s more, as irrigation becomes more necessary because of drought, investments in the most essential commodity – water – could see an uptick.

Finally, with crop yields in traditional farms under threat due to climate change, there’s an opportunity to invest in companies that grow food in indoor settings. Two areas that stand out here are vertical farming and lab-grown meat.