Major central banks are offloading huge stashes of government bonds in a process called quantitative tightening (QT). And investors have been anxious about the repercussions, including a dropoff in global liquidity, a rise in borrowing costs, and damage to market functioning.

However, a new study looked at eight instances of QT and concluded that this important central bank tool has actually been working as intended, and without major impacts on market functioning and liquidity. What's more, the study found that announcing the start of QT caused just a modest increase in bond yields.

Having said that, QT programs are only one piece of the puzzle for bonds, and there are other, more unsettling concerns in the market. Right now, for example, investors are starting to worry about a potential debt crisis in the US – a possibility that deserves more of your focus.

Investors are anxiously watching as central banks offload huge stashes of government bonds and other assets, batch by batch. And it does seem like reason enough to worry: shrinking central bank balance sheets are typically associated with a drop off in global liquidity, a rise in borrowing costs, damage to market functioning, and more. Fortunately, the fallout tends not to be as severe as people fear, according to a new study.

How did we get here in the first place?

It started with quantitative easing (QE): an unconventional stimulus tactic in which a central bank purchases vast amounts of government bonds and other assets from the open market using newly printed money. QE went mainstream in 2008 when major central banks all over the world launched their own bond-buying programs in response to the global financial crisis. The goal was to use QE to stimulate the economy by lowering interest rates and increasing the supply of money, both of which encourage lending and, in turn, spending, investments, and other activities that help spark growth. And, generally, the plan worked.

QE returned to prominence in 2020, in response to the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic – this time reaching an even bigger scale. Over the course of two years, the Federal Reserve (the Fed) snapped up $3.3 trillion in US government bonds and $1.3 trillion in mortgage-backed securities. By March 2022, the US central bank owned a quarter of all outstanding Treasury debt and a third of mortgage-backed securities. The European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England (BoE) each owned just shy of 40% of their countries’ government bonds, while the Bank of Japan (BoJ) owned nearly half of its nation’s government debt.

But the soaring inflation that hit after economies lifted pandemic-era restrictions cornered officials into not just letting up on those QE programs, but actually reversing them – that is, shrinking their balance sheets via “quantitative tightening” (or QT). Central banks in the US, Europe, Canada, and Australia opted for a passive QT approach – not buying new bonds when their existing ones mature. The Fed, for example, has been letting $60 billion in Treasuries and $35 billion in mortgage-backed securities mature each month without replacement. Meanwhile, central banks in New Zealand, Sweden, and the UK started active QT (selling bonds outright). And all of this QT, happening at the same time, was expected to have huge repercussions on the world’s economies and financial markets.

So what kinds of things were supposed to happen with these moves?

The QT among the world’s major central banks would be expected to lead to a drop-off in liquidity – both kinds. First, there’s market liquidity: the amount of money in the global financial system that’s available for investors to access. As it shrinks, you might expect a dip in the prices of financial assets – because the less money there is swimming around the system, the more difficult it becomes for investors to buy them.

Second, there’s the liquidity of individual assets: the ease with which investors can buy and sell assets to one another without prices slipping. Investors have worried that the increased supply due to QT would dry up liquidity in bond markets, affecting their fundamental operations.

QT also has an effect that’s similar to the very conventional central bank tool of hiking interest rates: they both push up the cost of borrowing. The increased supply of bonds forces up their yields, which serve as benchmarks for other lending rates, from mortgages to corporate loans. In fact, according to an analyst at Société Générale, every $100 billion drop in the Fed’s balance sheet is equivalent to a rate hike of 0.12 percentage points, with the effects amplifying with each new reduction. Higher borrowing costs dampen spending and investments, which lead to lower economic growth.

So what does the new study say?

Since the pandemic, seven central banks have made meaningful progress in shrinking their balance sheets – on top of the Fed’s QT efforts from 2017-2019. The new study by two academics and the chief US economist at Deutsche Bank used those experiences to assess what happens when policymakers announce and carry out QT.

Seven central banks have made notable progress in reducing the size of their balance sheets. Source: Financial Times.

And what they found is good news: the QT programs have been working as central banks intended, at least so far. They’ve been operating quietly in the background, lending support to central bank efforts to combat inflationby restraining financial conditions, but without major repercussions for market functioning and liquidity. Put differently, QT has worked in the opposite direction to QE, but with effects that have been much more muted.

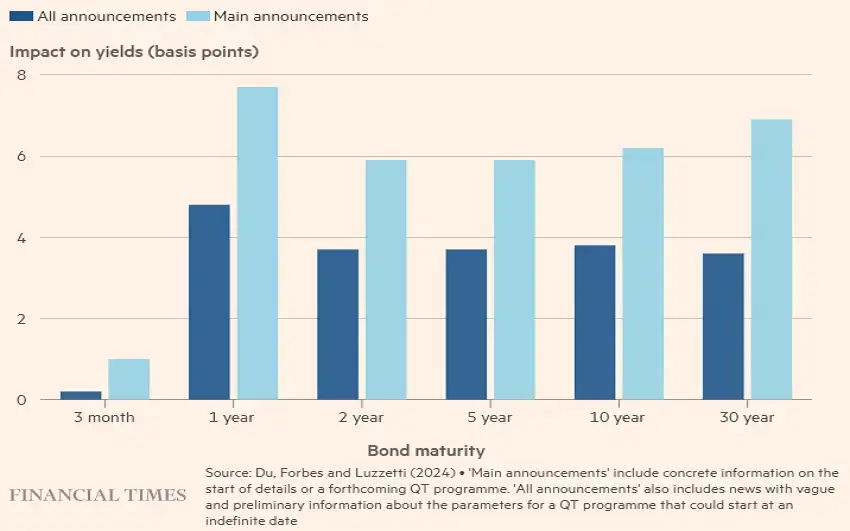

Interestingly, they also found that simply announcing the start of QT was enough to cause a modest increase in yields (0.04 to 0.08 percentage points) in government bondswith maturities of one year or longer. And the type of QT announced determined how the impact played out. Passive QT seemed to provide a signal of the central bank’s commitment to tighter monetary policy, which then increased shorter-dated yields – the ones at the short end of the yield curve. Active QT announcements, meanwhile, mainly increased yields of longer-dated maturities, steepening the curve.

Impact of QT announcements on government bond yields at different maturities. Source: Financial Times.

The research may come as a relief for central banks: huge holdings of bondsin some places are creating headaches as higher interest rates translate to big losses. Still, central banks have been hesitant to unwind their holdings on a huge scale, as they’ve had little evidence about the potential fallout. After all, QE had an enormous effect on financial markets – lowering interest rates, raising stock prices, and removing liquidity pressures. If QT were to have similar effects in reverse, it might undermine any economic recovery. It’s why central banks were reluctant to start QT back in the 2010s, in the hard-fought recovery from the global financial crisis.

So what does this all mean for you?

There may not be any direct investment ideas to take away from this study, but it should give you some comfort in knowing that central banks’ QT programs are unlikely to cause significant market disruptions or lead to an unwieldy jump in yields.

Having said that, it’s also worth bearing in mind that QE and QT programs are only one piece of the puzzle for bonds, and there are other, more unsettling worries in the market. Right now, for example, investors are starting to fear that the US debt load is on an unsustainable path, with the amount the country owes, relative to the size of its enormous economy, at a high never seen outside of wartime. It’s a situation with the potential to trigger a debt crisis for the world’s biggest economy.

Such a scenario would arguably have a bigger impact on bond markets than the Fed’s current QT program, and so it deserves more of your focus. To better understand the current issues with the US’s escalating debt burden and how you can adjust your portfolio accordingly, check out Stéphane’s Insight. He points to assets that could do well even if a US debt crisis develops, such as gold, bitcoin, real estate, and commodities.

-

Capital at risk. Our analyst insights are for educational and entertainment purposes only. They’re produced by Finimize and represent their own opinions and views only. Wealthyhood does not render investment, financial, legal, tax, or accounting advice and has no control over the analyst insights content.