Commercial property prices are down about 20% from their peak, with office buildings in business centers taking an even bigger hit, losing almost half of their value.

The full impact of those plummeting prices likely hasn’t kicked in yet. When it does, it will put borrowers under stress and lenders too – particularly small, regional, commercial banks.

In theory, that shouldn’t pose a threat to the whole financial system. But that’s what people said just before the 2008 global financial crisis. And there are plenty of reasons for worry.

US commercial real estate is casting a skyscraper-sized shadow over its lenders worldwide and raising worries about a potential crisis. German lending giant Deutsche Pfandbriefbank has been struggling to reassure investors over concerns about its exposure to this struggling market. And banks from New York to Japan are dealing with similar fallout, with fears about a broader contagion blast higher like an elevator.

What’s going on?

Commercial real estate holds a high, towering place in the overall property market – sweeping under its roof not just traditional downtown office buildings, but also retail, industrial, and multifamily properties. All of that saw a huge boom over the past decade, fuelled by low financing costs that made it easy for developers, investors, and banks to finance and invest in new properties.But then, two things happened. First, the pandemic-era work-from-home practices changed office work patterns, leading to record vacancy rates and cutting the demand for office buildings (as well as linked sectors like hotels, retail stores, and condos in commercial areas). Second, central banks aggressively hiked interest rates to tame inflation that had reached skyscraper heights. That made real estate investments a lot less attractive, relative to a far safer cash account, and placed financial strain on both owners and tenants, ultimately decreasing demand.Prices have been plunging ever since, as I warne

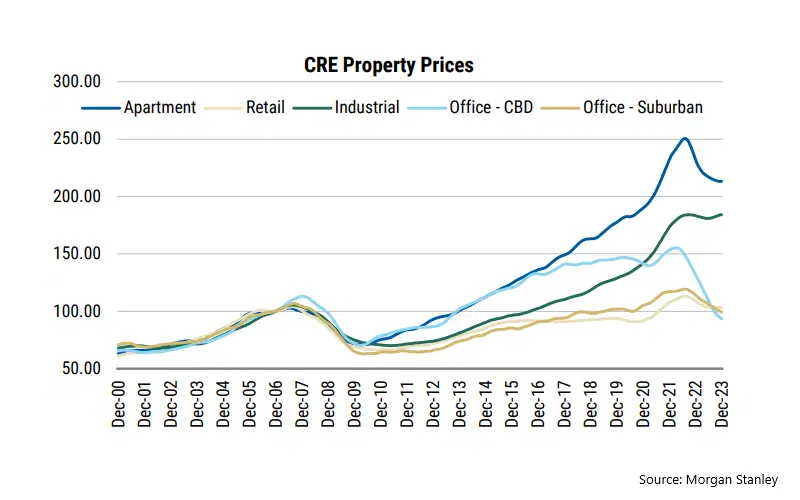

d about then. It’s difficult to precisely gauge the extent of the damage since transactions (the few still happening) are done privately and often include short-term clauses that complicate their valuations. It’s clear, however, that office buildings in central business districts (light blue line) have taken the biggest hit, losing almost half their value, according to research from Morgan Stanley. The fall has been painful but less dramatic across categories like apartments and retail, while industrial properties have remarkably barely dipped.

Property prices of different commercial real estate types. Source: Morgan Stanley.

Overall, commercial property prices are down about 20% – that’s similar to the 21% hit it took during the US savings & loan crisis in the early 1990s, but not as steep as the nearly 40% hit from the 2008-09 global financial crisis.

Of course, there’s no guarantee the drop will stop here. Property prices do tend to move in slow cycles because supply and demand take time to adjust. But there are encouraging signs that the worst may be over: deal volumes are picking up, lending standards are easing, and the economic picture has been improving.

What’s the issue, then?

The issue is that these things can take years to play out and the true impact of those plummeting prices likely hasn’t fully hit us yet. What’s more, the trouble brews on both sides of the coin: borrowers and lenders face risks.

Borrowers might default when they need to refinance. Up to $1.5 trillion of commercial mortgages will mature over the next two years. That’s a quarter of all commercial mortgages out there – a peak not seen since 2008. And the issue is, these loans will need to be refinanced at interest rates that are significantly heftier than before – we’re talking two to three times higher, thanks to those aggressive interest rate hikes. Borrowers caught in this bind could struggle to secure refinancing and may have to scramble for alternative lending sources, come up with more money, or be pushed into selling. For the less resilient among them, defaulting may become a reality.

Lenders are facing a dangerous rise in defaults. Small banks in the US are particularly exposed, holding almost 70% of all outstanding commercial real estate (CRE) loans. These loans represent a chunky 44% of their entire lending portfolio. Bigger banks, by contrast, are in a more cushioned position, with CRE loans only 13% of their loan books. And, sure, if those borrowers default, the lenders could take control of those properties, but in many cases, they’re worth a lot less, so that’s not much comfort. To prepare for those losses, then, banks around the world have been stockpiling more reserves, and raising eyebrows in the process, since that suggests we might be getting closer to that stage.

Of course, the issue isn’t just confined to US banks. Banks everywhere have been riding the commercial real estate bull market, both in America and at home. Among European banks, for example, commercial real estate accounts for 9% of all loans (and about 15% of all loans where the borrower has missed a payment).

So, are we headed for a crisis?

Of course, that’s not a simple question to answer. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen have said they expect stress in commercial real estate to inflict some damage on particular lenders, but neither believes it will pose a major “systemic” economic risk for the US or world economy. In other words, you could see some rough sledding for some smaller, commercial banks, but not a 2008-style avalanche that brings down the economy, the stock market, and the global financial system.

Problem is, that’s just what people were saying right before the global financial crisis. Case in point: then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke said subprime lending and housing market weakness didn’t pose a systemic risk to the financial sector, just a few months before they took down the overall financial system.

My point is this: it’s important to be humble – and cautious – when it comes to assessing the risks to our financial system. And right now there are a few things that trouble me:

Small commercial banks are the heart of the US economy. They provide vital credit to small and medium-sized businesses, which, in turn, account for around 40% of the US economy and job market. If they come under stress, it could spread to the rest of the economy.

It’s hard to know how troubled CRE actually is. It’s a niche, opaque market. And the more opaque the market, the more likely investors are to “sell first, ask questions later”.

Crises aren’t all about fundamentals: they can also be about confidence. Silicon Valley Bank was facing a manageable liquidity issue, but a sudden mass withdrawal by depositors escalated the problem into a fatal crisis. Perception can have major consequences for financial institutions, turning solvable problems into systemic threats.

Exacerbating factors like poor liquidity, forced selling, or a mismatch between asset values and what’s owed on them can quickly turn a situation from bad to worse. And the financial system’s interconnectedness means that issues in one area can rapidly affect seemingly unrelated sectors.

There are two dangerous feedback loops here. The first is between banks and commercial real estate prices: when small banks face more defaults, they cut back on lending, which stresses property owners and then worsens the banks’ problems. And the other is between bank stock prices and their fundamentals: falling prices worsen banks’ regulatory ratios, which lower sentiment, leading to lower stock prices, and so on.

The safeguards put in place in the financial system after the 2008-09 crisis remain mostly untested. And a lot of this market’s loans have moved, along with their risks, to “shadow banks” – private equity funds, private lenders, hedge funds, and so on. Those entities are less regulated and more opaque, so their risks are harder to assess.

And, finally, good news may be bad news: a strong economy can support inflation and that means the epicenter for the strain here – that is, higher interest rates – probably won’t shift dramatically, at least not until the economy’s under some threat. And the longer interest rates remain high, the higher the risks of defaults in commercial real estate.

Look, overall I’d agree that the most likely scenario is that the stress from this market will be relatively contained and won’t lead to a repeat of the global financial crisis. But I also think investors are grossly underestimating the risks of such a scenario developing.

And the ultimate warning sign: private markets mover and shaker Blackstone has just made the cover of Forbes magazine. You know what that means…

-

Capital at risk. Our analyst insights are used for information purposes only.